Minutes from the Treaty of Fort Adams (Part 2)

Published August 1, 2024This month, Iti Fabvssa is continuing to examine the conversations between representatives of the United States and the Choctaw Nation by reviewing the minuets from the 1801 Treaty of Fort Adams. In last month’s Part 1, we followed the speech by U.S. Commissioner General Wilkinson to Choctaw Leaders. This speech communicated that the U.S. wanted to affirm peace and friendship with the Choctaw Nation, allow Choctaw leaders to share any issues that they may be having, make improvements to the Nache Hina, or Natchez Trace, so it would be suitable for wagon traffic from Natchez to (old) Cumberland, gain right-of-way access for the US government alongside the newly improved wagon road, establish another wagon road between Natchez and Mobile, and survey the boundary between the United States and the Choctaw Nation. The Commission also request that Choctaw Nation express thanks for the gifts that the President of the United States gave to the Choctaw Leaders despite the position that the US did not feel Choctaw Nation deserved the gifts.

Below, are the speeches made by the Choctaw Chiefs in response to General Wilkinson. Following the excerpts (italicized), we provide additional context. This transcript has been copied from the American State Papers Indian Affairs volumes.

“Tuskonahopia, a chief of the Lower towns, informed the commissioners that were seven chiefs from different towns, and requested, in their behalf, that they might be heard separately, that each might speak for this own town; and that, after they had spoken, the young warriors might be heard, and the same attention paid to their talks that would be to those of the old chiefs.”

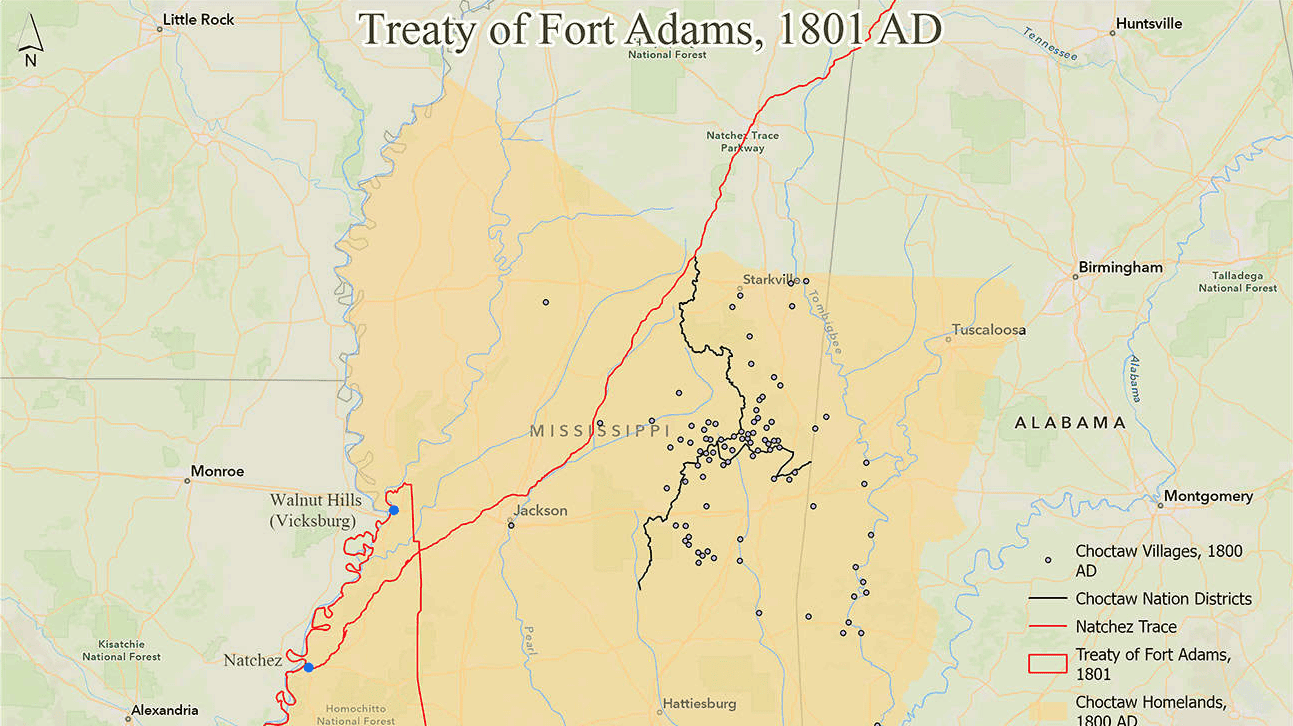

The Choctaw Nation of the ancestral homelands was divided into three districts: the Okla Falaia, or the Long People (referred to here as the Lower Towns); the Ahepvt Okla or the Spread-out Potatoes People (referred to as the Upper Towns); and the Okla Hannali, the Six Towns People. Each of these districts were made up of several towns and many villages. During diplomatic negotiations, the villages would send a Chief to represent the town or a collection of towns.

Choctaw men followed a social hierarchy: Chiefs > Beloved Men > Warriors > Young Men. During talks, this social hierarchy dictated who spoke first. Tuskonahopia illustrated this by stating that the Chiefs would be given the opportunity to speak first while the warriors in attendance would be given the opportunity to speak afterwards. Among the Chiefs, Tuskonahopia was given the honor of speaking first because he was the most respected Chief attending the negotiations.

Tuskonahopia then spoke: To-day I meet the commissioners here, who have delivered to us the talks from the President, and I am well pleased with his talks, that I have received from my beloved brothers the commissioners, for the welfare of my nation. I take you three beloved men by the hand, and hold you fast. You three commissioners, who have visited the Cherokees and Chickasaws, one request which you ask of my nation, the cutting of a road, I grant. I grant it as a white road, as a path of peace, and not as a path of war; one which is never to be stained. I understood yesterday, that my father the President allowed me an annual present, and it never should be taken from me. It must have been a mistake of his officers, as I never have received any annual allowances. He must have given it to some other of my red brethren, I deny having received any annual gift. It has been told the chiefs of the nation, through the interpreters, that their father allowed them an annual present for their nation.

I forgot something when I spoke of present, which I will now mention. We have received presents from our father the President; part at the Walnut Hills, and part at Natchez. I, myself, and a few other chiefs, and a few warriors, went to the Walnut Hills, and the presents were but very small. I do not know whether these presents were concealed from us or not; but I Know we got but a few, not worth going after. A company of the war chiefs and warriors received, the last spring past, a few presents at the Bluffs that is all; if there have been any other given, it must have been to idle Indians, who are straggling about, and do not attend to the talks of the chiefs of the nation.

There is an old boundary line between the white people and my nation, which was run before I was a chief of the nation. This line was run by the permission of the chiefs of the nation, who were chiefs at that time; they understood, when that line was run, that they were to receive pay for those lands; but they never have received pay for those lands. These chiefs, here present, acknowledge the lands to be the white people’s land; they hold no claim on it, although they never received any pay for it; they wish the lands to be marked anew, and that it be done by some of both parties, as both should be present; (meaning read and white people).

Miko Tuskonahopai was from the Okla Falaia District. To summarize his speech, he, granted the Americans permission to make improvements to the trade road. In Choctaw Culture, white was the color of peace and red the color of war. He stated that the road was to be white, meaning to be utilized in peace and friendship with the U.S. and should never be used as a pathway for the Choctaw Nation or the U.S to war with each other.

In Part 1, we discussed that the U.S. Commissioners told Choctaw Leaders that the President had delivered annual gifts to them as a token of friendship and that the Choctaw were not deserving of these gifts, and that they should thank the President for his generosity. However, from the perspectives of the Choctaw Leaders, the gifts were rent paid by the United States for utilizing Choctaw Lands. In earlier negotiations with the British and Spanish, Choctaw leaders orally stated that lands would be shared. However, the British and Spanish wrote into their treaties that the lands were ceded by the Choctaw. This deceit resulted in the U.S believing that it now owned these lands and that it needed to make no payments to the Choctaw Nation.

Tuskonahopai tactfully approached the topic of gifts. He first feigns that he had never received gifts from the President. He then pivoted and stated that he had received gifts from the president at Natchez or Walnut Hills (old name for Vicksburg), however the gifts were so insufficient that they were not worth his time to travel to collect them. He stated that if the gifts from the President were so great, then they must have been hidden from him or accidentally given away to others.

In 1786, the Choctaw Nation met with the U.S. at the Treaty of Hopewell. There, the United States established peace, friendship, and trade with the Choctaw Nation. This treaty, and others, recognize the Choctaw Nation as a sovereign nation and still contributes to our federal recognition today. The Boundary of the Choctaw Nation was also defined, based off the Treaty of Mobile with the British in 1768. Instead of being ungrateful for the presents from President Jefferson, the Choctaw leaders are being generous and powerful by not requiring compensation from European powers that rightfully belong to Choctaw Nation. According to Tuskonahopai, the Choctaw Nation never received compensation for Choctaw lands that were being occupied to the Americans. Using these facts, he negates the U.S attempt to make the Choctaw Nation look small and petty. He then states that the new boundary line must surveyed by both the Choctaw and U.S. representatives.

Too-te-hoo-muh from the same district, then spoke: I thank the President, my father, for sending you three beloved men here, to speak to me. I take you by the hand, hold you fast, and am going to speak to you. I grant this road to be cut, which the chief who spoke before me granted. I grant the road only; you may make it as firm, as good, and as strong, as you will; there are no big water courses on it, and there is no occasion for canoes or ferries. I speak now concerning an old line, which was run when I was a boy; I wish for this line to be traced and marked anew; I do not know where the line is; I have been informed, by some of the young men of my nation, that there are white people and stock over it. We, chiefs of the nation, wish, if any are over our lines, that they may be moved back again by our brothers, the officers of the United States, and that they would move them back, with their stock.

Miko Tootehoomuh, from the Okla Falaia District, also granted the trade road to be improved upon, however he did not grant the U.S. the right—of-way alongside the road. The United States wished access to the right-of-way alongside the road to build stage stations and ferries. The U.S. attempted to entice the Choctaw Leaders by allowing them to rent these businesses and retain the profit. Tootehoomuh stated that there are no major river crossings for ferries along the road, so he therefore denies the U.S. right-of-way. He then spoke about the boundary line and how Americans are illegally squatting on Choctaw lands. He requests that the U.S. to move their settlers off Choctaw lands once the boundary is marked. At this time, American livestock were quite detrimental to the carefully tended ecosystem that Choctaw people stewarded. Choctaw lands suffered from the effects of cattle brought by illegal American immigrants and he asked that these be removed.

Mingo-poos-coos of the Chickasaw half town: I am an old acquaintance here; I came here with other chiefs of the nation, not to differ with them, but to join them in whatever they do. I understand this business plainly; you three, sitting here, were sent by our father, the President, to speak to our nation. My talks are not long. I am here before three beloved men. I am a man of but few words in my town; it is the lowest but one in my nation. My talks are not long; I hope this will be considered as if I had said a great deal. The first time I ever saw my friend, the General, (Wilkinson) he appeared as if he wished to say a great deal; I objected, I was but one; I am a well wisher; the day will come when we head men will see each other. The road through our land to Tombeckbe, is not in my power to grant, there are other chiefs who hold claims on those lands; my claim is but short. The white people travel the line of limits; they are free to use that, and any of the small paths.

Miko Pooscoos is possibly from the town on Kushak, meaning Reed Brake. Kushak was part of a small group of villages in the northeastern part of the Okla Hannali District. The Okla Hannali District was a confederation of different Choctaw speaking people who moved into the Choctaw Nation in the 1600s and early 1700’s. Pooscoos notes that his village was the “lowest” meaning that it was not strong politically. He did not have the authority to grant the Americans access to the southern trade path because those lands were controlled by the other Six Towns District groups that were farther south. Pooscoos stated that the trade paths the Americans are already using south of Choctaw lands are sufficient.

Oak-chume, of the Upper town, spoke thus: I see you to day, in the shade of your own house. I am a poor distressed red man; I know not how to make any thing; I am in the place here from the Upper towns; my uncle was the great chief of the nation; he kept all paths clean and sweapt out; long poles of peace, a number of officers and chiefs in his arms; he is gone; he is dead, he has left us behind. You three beloved men in my presence, I am glad to see you; you may be my father for what I know; the Great Spirit above is over us all. I hold my five fingers, and, with them, i hold yours; mine are black, but i Whiten them for the occasion. I understood your great father, Washington, was dead, and that the great council got together and appointed another in his stead, who has not forgot us, and who love us as our father Washington did; and I am glad to hear our father, the President, wishes that the sun may shine bright over his red children. The Chickasaws are my old brothers; you visited them, and talked to them, before I saw you here. I understood you asked them for a big path to be cut, a white path, a path of peace, and that they granted it to you, as far their claims extend. I grant it likewise. There are no big water-courses, there are no big rivers, nor creeks, and therefore, no occasion for canoes, nor is there any occasion for horse boats. It is not our wish that there should be any houses built; the reason I give is, that there is a number of warriors who might spoil something belonging to the occupiers of those houses, and the complaints would become troublesome to me, and to the chiefs on my nation. I speak next of our old line; I wish it to be traced up, and marked over again; I claim part in it; those people who are over it, I wish back again, for fear they may destroy the line, and it be lost. I have done.

Miko Oakchume, of the Okla Falaia District, began by humbling himself to the U.S. commissioners. He mentioned that his uncle was a great chief, perhaps a reference to Chief Franchimastubbe who recently passed away. He states that his fingers “…are black, but i Whiten them for the occasion” which indicates that he is a War Chief, but was not acting in that role for these negotiations. Oakchume, like Tootehoomah, granted the improvement of the road, to be used for peace, but not for the United States to access the roads’ right-of-way. He then cautioned that having American people so close may entice the younger warriors to raid the homes along the wagon road and that would cause many issues. He wished the boundary line to be surveyed so that it is not lost again.

Puck-shem-ubbee, from the Upper towns, then spoke: The old line that the other chiefs repeated, as far as I understood from my forefathers, I will name its course, and the water-courses it crosses, beginning at the Homochitto, running thence nearly a northwest course, until it strikes the Standing-pines creek; thence, crosses the Bayou Pierre, high up, and Big Black; from thence, strikes the Mississippi at the mount of Tallauhatche. (Yawzoo.) That line I wish may be renewed, that both parties may know their own. There are people over, or on the line; it is my wish they may be removed immediately. Where the line runs, along the Bayou Pierre, some whites are settled on this line, and some over it; those over, I wish may be removed; if there are none over, there is nothing spoiled. From the information I have received from my forefathers, this Natchez country belonged to red people; the whole of it, which is not settled by white people. But you Americans were not the first people who got this country from the red people. We sold our lands, but never got any value for it; this I speak from the information of old men. We did not sell them to you, and, as we never received anything for it, I wish you, our friends, to think of it, and make us some compensation for it. We are red people, and you are white people; we did not come here to beg; we brought no property with us to purchase any thing; we came to do the business of our nation and return.

The other chiefs have granted you this road. We do not wish the white people to go alone to make the road; we wish a few of the red people, and an interpreter, to go with them. We, of the Upper towns district, a large district, I speak for them now: there is but one interpreter in our nation; he is a long distance from us; when we have business to do, we wish to have our interpreter near. It is the wish to have, for the Upper towns, an interpreter from among the white people who live with us, that we may do our business with more satisfaction with the chiefs of the district. I have another request to ask of you, for the distresses of our nation; a blacksmith, who can do our work well, for the Upper towns district. Another thing I have to request, for our young women, and half breeds; we want spinning wheels, and somebody to be sent among them to teach them to spin. I have nothing more to say; I have complied with the request of the commissioners; I have done. Further I have to ask, concerning the blacksmith and tools; if the man leaves us, let him leave his tools, and that they may remain with us, as property of the Upper towns district.

Miko Puskshemubbee of the Oklahoma Falaia District stated the boundary line as was told to him by his elders. He also wished for the line to be surveyed because there may be American squatters living across it in the Choctaw Nation; if so, they must be removed. He then reminded that the Natchez District was never sold to the U.S. and if they wished to have it, they must pay for it. He stated that the Choctaw Nation did not come to the negotiations to beg or purchase anything, but to do business and go home.

E-lau-tau-lau-hoo-muh spoke thus: I am a stranger; this is the first time I ever saw the Americans. I came here, I am sorry that it appeared cloudy, but it has cleared off, (alluding to the cloudy weather, which cleared off just as he began to speak.) I understood; by what I have heard, that you are authorized by our father to come and talk to us. I am glad to take you by the hand, which I do kindly, and am glad our father, the President, thinks of his red children. It is my wish, with the rest of the old chiefs, that the line may be marked anew. There is a number of water courses in our land, and I wish the white people to keep no stock on them, or to build houses. I am done; my talk is short, and I will shake hands with you.

Miko Elautaulauhoomuh began by apologizing for the cloudy weather. In Choctaw culture, all political negotiations would be done under full sunlight. At this time, Choctaw people believed that the sun was the eye of God and that no one would speak a lie in front of God. Like the other chiefs, he reiterated that he wished for the boundary line to be surveyed and did not give permission for a right-of-way to the wagon road.

The interpreter then stated, that the chiefs directed him to inform the commissioners, the young warriors wished to be indulged with making their talks on paper, at their encampment, if that would do, and to be supplied, for that purpose, with paper. It was ordered accordingly, and the commissioners adjourned.

The Choctaw Chiefs, after their speeches, wished to give the warriors the opportunity to speak. Since the time for negotiations was over, the Chiefs asked that the warriors be allowed to record their speeches on paper and they be provided to the Commissioners. Next month, in Part 3, we will get to read speeches.

When we study the situations and decisions of our ancestors, we can see the future they wished for us to have. As we read their words, we can see how Choctaw culture informed their thoughts, feelings, and perspectives. Next month Iti Fabvssa will continue sharing the meeting minutes from the Treaty of Fort Adams (Part 3). If you would like to jump ahead, we encourage you to look at the American State Papers. Class II Indian Affairs. Volume 1. Pages 658-663.