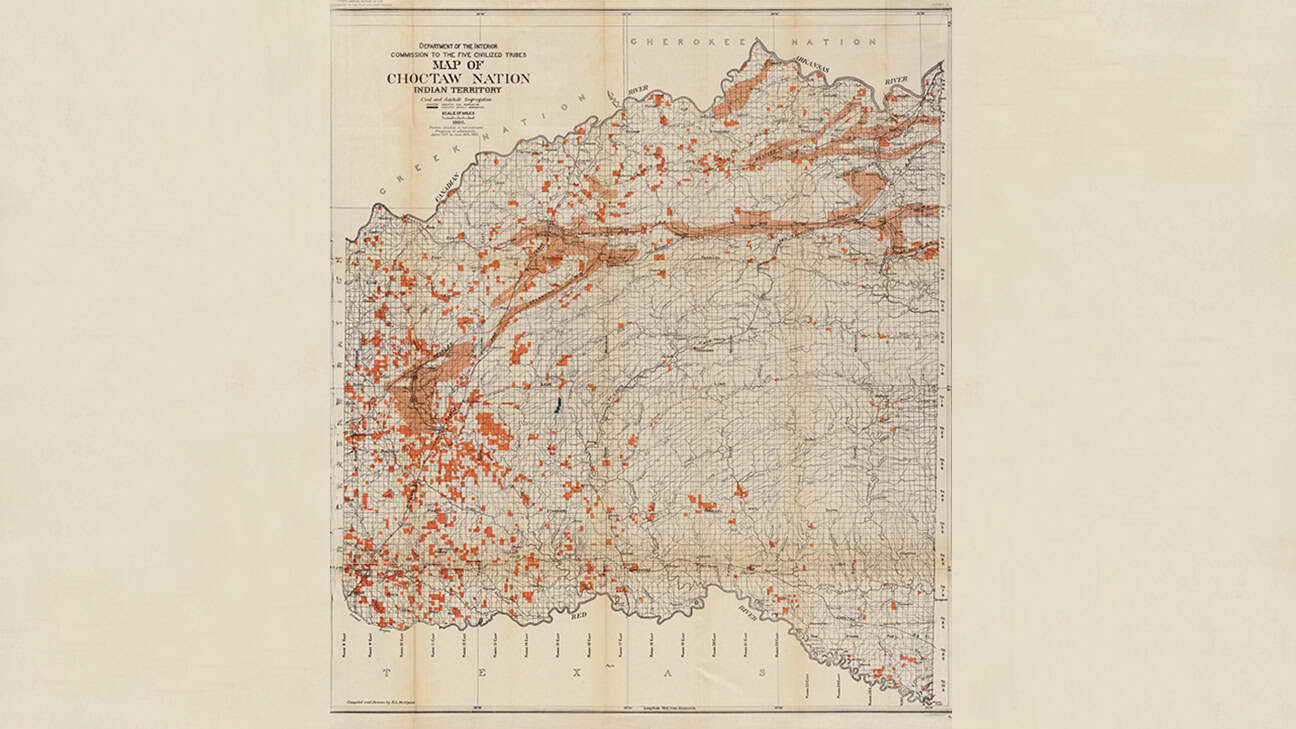

A map of Choctaw Nation, Indian territory, coal and asphalt segregation.

Coal in Choctaw Nation, Part I

Iti FabvssaPublished January 3, 2025By Megan Baker, Guest Writer

While casinos have been one of Choctaw Nation’s most successful business endeavors, a lesser-known Choctaw economic project was their venture into the coal mining industry. As the United States and other nations over the world industrialized in the 1800s, coal became a high demand natural resource due to its efficiency compared to lumber. Concentrated in the northern half of Choctaw Nation, coal and its mining has shaped many communities and the history of the region. From the mining camps that became towns to the establishment of Little Italy, coal mining has had a clear legacy. In this three-part series, Iti Fabvssa will delve into the history of Choctaw coal and its mining to highlight its role in sustaining the sovereignty of the Choctaw Nation in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

Coal has long been known to exist in the region that is now the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma. When the French explorer Bernard de La Harpe travelled through these lands in 1719, he noted that there were “many deposits abundant with coal” near a stream now known as Coal Creek.¹ Surveyors employed by the US government to document the lands before and after the removal of the Five Tribes to Indian Territory also recorded the abundant presence of coal. As Choctaws settled into their new territory, they used coal found at the surface of the land for fire. Some enterprising individuals gathered coal, loaded it in wagons, and sold it as far away as Fort Sill and Arbuckle.² Choctaws named the county where coal was found ‘Tobocksey,” based off the Choctaw word for coal, “tobaksi.”

Since removal, the Choctaw government had undergone massive changes to rebuild their government. Between 1830 and 1872, the government had ratified multiple constitutions, integrated in Chickasaws into the Choctaw government, allowed Chickasaws to have their own government, and massively expanded the number of courts, schools, and other government offices. Choctaws’ experiences with the US government had clearly taught them the value of integrating some aspects of Western society into Choctaw government in order to protect their way of life.

While some things in Choctaw society changed, other aspects did not. One of those aspects that is also key to understanding the history of Choctaw coal mining was the Choctaw system of land ownership. Unlike the US land ownership model that emphasizes exclusive rights, Choctaws’ land ownership in the 1800s was rooted in the Choctaw philosophy of communal land ownership which had been followed for thousands of generations. Families usually lived on plots of land that they could reasonably use and cultivate. For Choctaw people living within treaty territory, there were no absolute titles; rather, if someone stopped taking care of land that they claimed, it would go back to the community. One individual who lived in Choctaw Nation in the 1800s stated that “there were no fences in the country in those days.”³ By not viewing land as an object that could be owned, Choctaws continued to uphold old Choctaw values in the new homelands. Furthermore, to protect Choctaw lands from outsiders, Choctaw government established an intricate permit system that regulated non-Choctaw citizens who sought to work and live within Choctaw territory. But some individuals would find ways to undermine this system.

One non-Native businessman was able to manipulate Choctaw Nation’s permit system. While he lived in Arkansas, he worked with a surveyor who noted the vast amounts of coal in Choctaw territory and provided him with a map of coal outcroppings. This knowledge convinced him to move to the Choctaw Nation, apply for a permit to sell goods and wares, and acquire land that he could then lease to a mining company. But since only Choctaw citizens could claim and lease Choctaw lands, he had to first marry a Choctaw or Chickasaw citizen living in the Choctaw Nation to become an “intermarried Choctaw citizen.” Once he gained Choctaw citizenship through marriage, he was able to claim parcels of Choctaw lands that the surveyor maps had shown to have coal beneath the surface. Then, he, other intermarried citizens, and two Choctaws worked together to enter into contracts with companies to mine coal and provide each of them with a share of the profits. Alongside this, the Choctaw government also had to deal with issues regarding the US Civil War.

Before Choctaws signed their post-Civil War treaties in 1866, railroad companies were blocked from entering Indian Territory. But since the Choctaws’ alliance with the Confederacy had failed, the US government punished the Choctaw Nation with a new, disadvantageous treaty. In the Treaty of 1866, Choctaw Nation had to agree to an allowance of one north-south and one east-west railroad to pass through its lands. This ultimately led to the construction of the Missouri, Kansas, and Texas Railroad through Choctaw Nation. Its completion and opening in 1872 was a critical moment in Choctaw history because the railroad brought in many outsiders into Choctaw territory. Many intermarried whites who prioritized business over maintaining traditional Choctaw lifeways, welcomed the railroad because it could transport coal out of Choctaw Nation to markets across the United States.

In 1875, the Osage Coal and Mining Company (no association with the tribal nation) opened the first commercial coal mine in Choctaw Nation.⁴ This mine was made possible because of the contract signed by non-Native businessman discussed above. As the leaser, the businessman and individuals who followed his example received money from the lease as well as royalties on the extracted coal. While he and other men got rich from this endeavor, these coal mines also brought in many outsiders to work in them. This massive influx of outsiders and rapidly growing industry would cause major problems for the Choctaw government that now would need to regulate both.

In Part II, Iti Fabvssa will cover the problems that arose from the introduction of the mining industry and how the Choctaw government sought to make coal mining an endeavor that could benefit all Choctaw people rather than a select few.

Works Cited

- Anna Lewis, “La Harpe’s First Expedition in Oklahoma, 1718-1719,” Chronicles of Oklahoma 2, no. 4 (1924): 331–49.

- Harris, Amelia F. “Interview with Mrs. Arthur Walcott,” Indian Pioneer Papers, Volume 94: 228.

- Bolinger, Bradley. “Interview with John E. McGee,” Indian Pioneer Papers, Volume 58: 140-143.

- Gene Aldrich, “A History of the Coal Industry in Oklahoma to 1907” (Norman, University of Oklahoma, 1952).