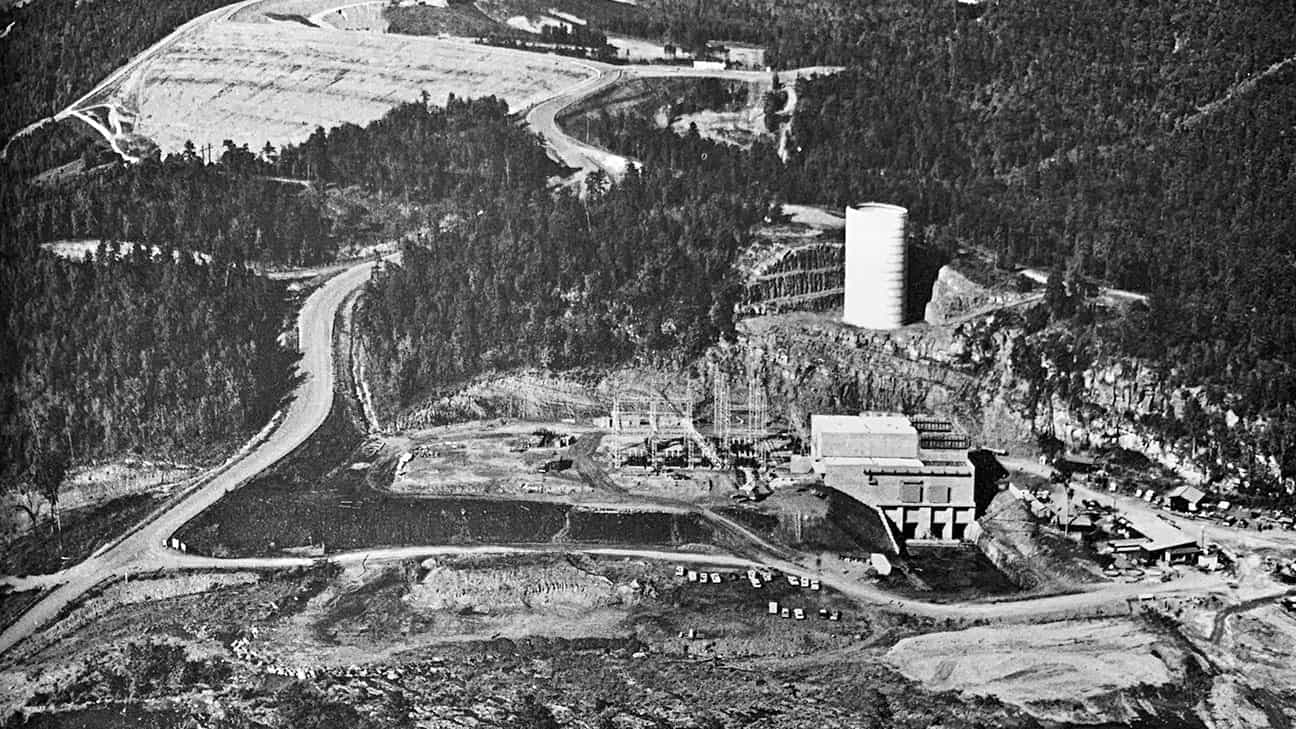

Aerial view of the construction of Broken Bow dam, which was proposed for economic development in Southeastern Oklahoma, but which also came at a cost for Choctaw communities that were displaced for its construction.

A New Chahta Homeland: A History by the Decade, 1960-1970

Iti FabvssaPublished July 7, 2022Iti Fabvssa is currently running a series that covers the span of Oklahoma Choctaw history. By examining each decade since the Choctaw government arrived in our new homelands using Choctaw-created documents, we gain a better understanding of Choctaw ancestors’ experiences and how they made decisions that have led us into the present. This month covers the 1960-1970 period when legislation outlining the process for Choctaw termination was developed and passed into U.S. law.

One of the major plans to improve economic conditions in Southeastern Oklahoma was to build and improve infrastructure in the region. This meant building new roads and major projects like hydroelectric dams. Throughout the 1960s, the state of Oklahoma worked with the federal government to construct these dams. Some of these dams are now popular recreation spots like Broken Bow and Sardis. And while these projects created new economic activities by creating jobs in the region, it came at a cost for many Choctaw people. Dams like Pine Creek, Broken Bow and Sardis were constructed on people’s allotments and displaced communities that were established when Choctaws arrived in Indian Territory. This pushed people to move elsewhere, whether to larger cities or other nearby Choctaw communities.

The 1960s were also a period of growing awareness about American Indian issues across the United States. Native peoples from numerous tribal nations who moved to urban and suburban areas due to relocation (as discussed in last month’s article) would meet and create new Native communities. In these new multi-tribal communities, Native people shared their respective cultures and struggles that their communities experienced with one another. For years, Choctaws were told that assimilation would be best for them to become a part of American society, but they started to see that this was not true. Coupled with the fact that the Trail of Tears and other factors discouraged some people from practicing Choctaw traditions, many customs have slept for years. Interacting with Native people of other Indigenous nations rekindled many Choctaw people’s interest in their own culture. Choctaw scholar Michelene Pesantubbee argues that this helped spur Choctaw cultural revitalization – which we are still in the midst of today.

Choctaw people living outside of the reservation also created their own Choctaw communities in cities like Oklahoma City and Dallas. Families and church groups living elsewhere also became more involved in Choctaw politics as they learned about life outside Southeastern Oklahoma and from other Native people’s experiences. What often started out as social gatherings of Choctaws quickly became something more as people shared their struggles which were connected to Choctaw issues like per capita payments and allotments. Throughout this period, numerous Choctaw groups were created out of the grassroots community organizing that started in order to enact changes in the Choctaw Nation and for tribal members across the country.

One particularly significant community was the Choctaws living in Oklahoma City. In 1969, after they heard about the approaching 1970 deadline for Choctaw termination, Choctaws quickly began gathering to discuss this issue and its possible negative effects with all the Choctaws they knew – near and far. As mentioned in last month’s article and an article by Choctaw anthropologist Valerie Lambert, Chief Belvin advocated for the termination in order to stop the Bureau of Indian Affairs‘ management of Choctaw affairs and speed up economic development for Choctaws. They argued that the termination of the nation-to-nation relationship between the Choctaw Nation and the U.S. government would negatively affect the lives of many community members.

Despite Belvin’s intention to help, we now know that the recognized tribal designation is key. Termination pushed some Oklahoma City Choctaws to travel back to Choctaw treaty territory to inform family and friends about termination and rally against it. Choctaw political activists would speak at community and church events and circulate petitions against termination for Choctaws to sign. They created lists of all the Choctaws across the country and sent mailers informing people of what was happening. These events revealed how Choctaw churches served as community centers that were important sites of Choctaw political organizing and revitalization.

As more members of the Choctaw community learned about termination, Chief Belvin soon received more and more letters opposing termination and asking why he pushed for it. This led to robust and passionate exchanges back and forth between Belvin and community members. Choctaws also wrote letters of opposition to the Oklahoma congressional delegation pushing for termination, outlining the possible negative effects that termination would have on their lives. They wrote letters to the Bureau of Indian Affairs reminding federal officials of how Choctaws were forced to leave their ancestral homelands, walk the Trail of Tears and how they were supposed to have these new homelands forever. They criticized the federal government for violating the terms of treaties and demanded they stop trying to escape their duties and obligations to Native nations and peoples. These letter-writing campaigns organized by Choctaw communities were critical to the movement against termination.

Termination legislation passed in 1959 had several requirements to be completed before termination was complete. This included establishing a corporation to handle Choctaw affairs and finding the descendants of all Choctaw allottees. In the original schedule of the termination legislation, all of these requirements were supposed to be done by 1962. By 1969, Congress had to pass legislation to extend the deadline for termination three times because all the requirements had not been met. The Bureau of Indian Affairs, which was responsible for making sure all these conditions were completed, made little headway in accomplishing all these things. As Choctaws increasingly organized and made their opposition to termination known, the Oklahoma congressional delegation responded accordingly. Following what the Choctaw people actually wanted, Representative Carl Albert worked with Chief Belvin on new legislation that would repeal the termination legislation. This was the legislation that President Nixon signed the day before termination was supposed to take effect.

Although the repeal legislation was signed the day before termination, Choctaws were not in any actual danger of losing their government. Because the criteria for the nation’s termination had not been fulfilled, Choctaws’ nation-to-nation relationship with the United States would have remained in place – even if the repeal legislation had not been signed by President Nixon before the termination deadline. Nevertheless, the termination opposition movement was critical to Choctaw nationhood today.

Despite the turmoil caused by the termination saga, it was an incredibly important moment in Choctaw history. Termination showed that Choctaws would do whatever was necessary to protect our culture, history and homelands. Pride in being Choctaw shifted from a focus on heritage and a past version of the Choctaw government to pride in being an active member of a living nation that has been maintained by hundreds of generations of Choctaw people. Organizing against termination encouraged Choctaws to become involved in tribal government and reminded tribal leaders of the importance of accountability to their people. Collectively, Choctaws also reminded the federal government of their obligations to Native people. The increased numbers of people involved in the political process helped revive and reinvigorate involvement in Choctaw tribal politics.

This campaign against termination laid the foundation for re-organizing the Choctaw government and for it to reclaim greater authority which had been diminished at the beginning of the century. Next month, we will cover 1970-1980, when the Choctaw government became reinvigorated due to greater community involvement in tribal government and organizing.