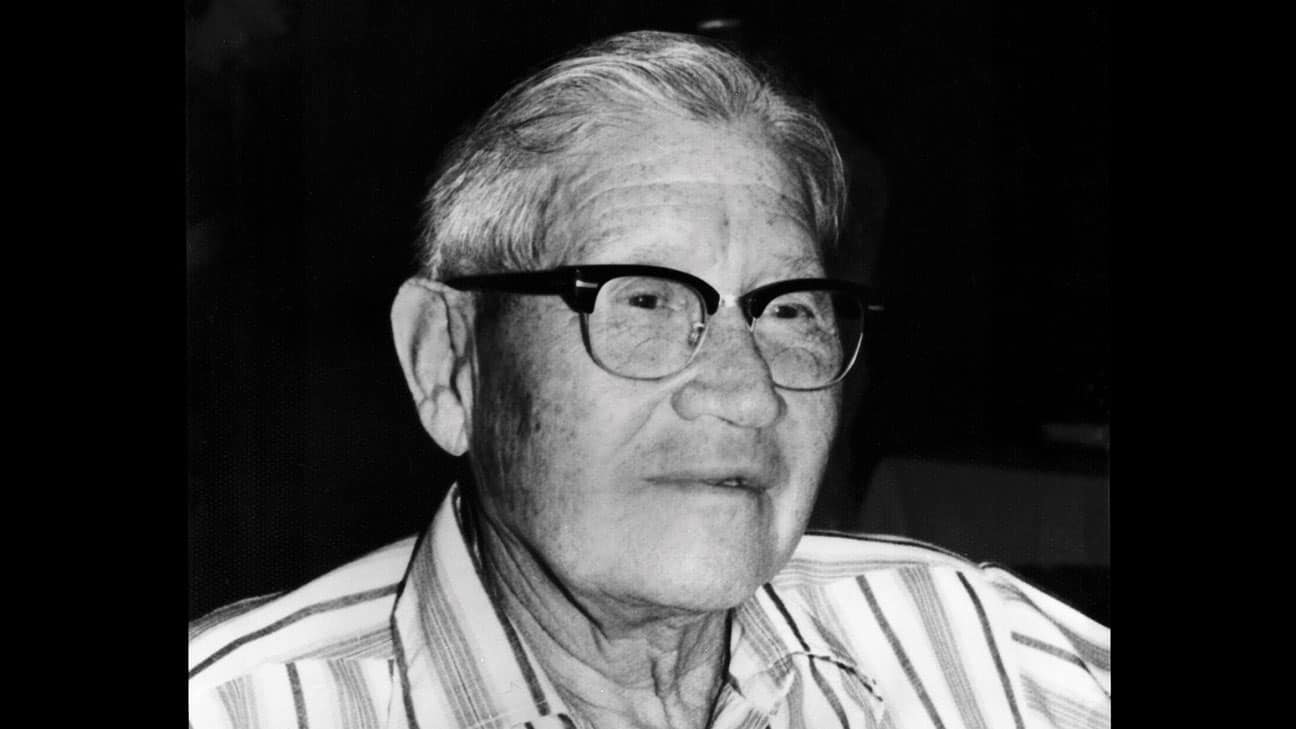

Chief Harry J. W. Belvin oversaw the development and passing of Choctaw termination legislation that would later be reversed.

A New Chahta Homeland: A History by the Decade, 1950-1960

Iti FabvssaPublished June 1, 2022Iti Fabvssa is currently running a series that covers the span of Oklahoma Choctaw history. By examining each decade since the Choctaw government arrived in our new homelands using Choctaw-created documents, we better understand Choctaw ancestors’ experiences and how they made decisions that have led us into the present. This month covers the 1950-1960 period when legislation outlining the process for Choctaw termination was developed and passed into U.S. law.

Many Choctaws were frustrated that it took 43 years for the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) to sell the Choctaw-Chickasaw coal and asphalt lands. Since Choctaws were supposed to receive per capita payments from the sale, the delay in the sale prevented many from receiving much-needed money. Many who were unaware of the complicated nature of this process came to believe that Choctaw chiefs were not doing their job – even though they worked diligently with other Choctaw leaders, BIA officials, members of Congress, and local state leaders to move the process along. In response, some Choctaw community members wrote letters to local Congressmen and BIA officials to complain about the chiefs. Some even went as far as to call for the abolishment of the office of the Choctaw chief and the dissolution of the relationship between the U.S. and Choctaw government. These misunderstandings about the nature of the duties and job of the Choctaw chief ultimately led to greater challenges for the Choctaw people to overcome as a whole.

Community frustrations with Choctaw leaders’ limited ability to respond to community members’ needs and concerns were used and cited by individuals in the BIA to push for termination. Beginning in the 1940s, the federal government began to pivot towards disestablishing tribal governments to assimilate Native people into U.S. society and its norms. In August 1953, U.S. Congress passed a resolution to “make the Indians within the territorial limits of the United States subject to the same laws and entitled to the same privileges and responsibilities as are applicable to other citizens of the United States, to end their status as wards of the United States, and to grant them all of the rights and prerogatives pertaining to American citizenship.” This resolution marked a new direction in federal policy regarding Native peoples. Across the United States, Native peoples grappled with poor economic conditions, which the 1928 Meriam report found to be the primary result of allotment. Moving beyond World War II, the federal government developed a policy that built upon previous laws like the Oklahoma Indian Welfare Act to help Native people. Strategies that became increasingly prominent were termination policies that would further disrupt Native communities.

In addition to termination legislation that aimed at ending the nation-to-nation relationship between Native nations and the U.S. government, a major and infamous termination-era policy was relocation. The Bureau of Indian Affairs-run urban relocation program was meant to solve the problem of poor economic conditions on the reservations while assimilating Native people into American society. The logic of this policy was to move Native people from reservations to major cities like Dallas, Chicago and Los Angeles so they could learn skills and gain employment. The BIA pledged to help people find housing and employment but in practice, the program often did not provide all of the support needed by Native people to make such a big move and life change. The relocation program, which began in 1952 and later expanded in 1956, caused major shifts in Native communities across the U.S. and contributed to building urban native communities.

Numerous Choctaws, faced with low economic prospects in Southeastern Oklahoma due to reliance on the low-wage economy, participated in relocation programs. Oklahoma City and Dallas were the primary local destinations for Choctaws. Throughout this period, many left Oklahoma to find work and opportunities unavailable in Choctaws’ new homeland. Military service also offered a way to leave the poverty that was increasingly becoming entrenched in rural Choctaw communities. As a federal policy, Relocation helps to explain why so many Choctaw community members live outside of our treaty boundaries. Despite the physical distance, some Choctaws maintained their connections to our Oklahoma communities and would travel back and forth. Others may have lost those connections, but many of them and their descendants are reconnecting with our Choctaw community today.

To help the Choctaws, Chief Harry J. W. Belvin went to court for financial compensation from the U.S. government for failing to fulfill their legal obligations to the Choctaw Nation. In 1943, the federal government set up the Indian Claims Commission as a venue for Native nations to bring lawsuits against the U.S. government. In 1951, Belvin took a case regarding the Net Proceeds and Leased District to the Indian Claims Commission for $753,609. The court’s rejection of the Choctaw suit motivated Belvin to organize a democratically elected tribal council and councils for each of the counties in Choctaw territory. This was ultimately rejected by the BIA area director and led Belvin to try to move away from BIA interference in Choctaw affairs.

Chief Harry J. W. Belvin worked with the Oklahoma congressional delegation to draft legislation that would restructure Choctaw Nation’s relationship with the federal government to reduce the BIA involvement with Choctaws’ daily lives. The legislative path to Choctaw termination differed from other Native nations slated for termination in the same time period since much of the push for it was initiated by Chief Belvin and a small group of Choctaws who thought such a separation would help their business interests. Initially, when Belvin proposed this legislation in his letters with the Oklahoma congressional delegation, he called for a policy that would give Choctaws greater management and control over their own lands and affairs. Belvin wanted to maintain Choctaw political distinctiveness, but through a legal entity like a corporation that would not be subjected to BIA oversight.

The law that the BIA officials drafted was different than what Belvin advocated for in his correspondence with the members of the Oklahoma congressional delegation and federal officials. The draft legislation proposed a wholesale termination of the Choctaw Nation. In congressional testimony years later, Belvin stated that the legislation that was read to and approved by a convention of Choctaw community members was different from the one that was approved and passed into law by Congress.

In 1959, the U.S. Congress passed an act that would become known as Choctaw Termination. This law outlined the procedure for what needed to happen to officially sever Choctaws’ nation-to-nation relationship with the U.S. government. The law stated that it would supplement the original 1906 act to provide for the final disposition of the affairs of the Five Tribes in Indian Territory by terminating only the Choctaws’ unique status as a nation. In the next decade, Choctaw community members would learn about this termination legislation while Choctaw leaders worked to wrap up Choctaw affairs. Covering 1960-1970, we will delve into the Choctaw efforts that stopped Choctaw termination.