Choctaw Resistance to Removal from Ancient Homeland (Part 3)

Iti FabvssaPublished August 1, 2014In May, Iti Fabvssa began a four part series, looking at different ways the Choctaw people resisted Removal from our homeland and the Trail of Tears. First, we looked at armed resistance. Last month, we looked at ways Choctaw people resisted signing the Dancing Rabbit Creek Treaty that ceded the last of the Choctaw homeland, setting up the Trail of Tears. This month, we focus on Choctaw individuals who, after the Treaty was signed, refused to remove from the homeland.

Several articles of the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek granted land to named Choctaw individuals, to men bearing certain leadership titles in Choctaw society, to Choctaw people who had land under cultivation, and to Choctaw orphans. In addition to this, under Article 14 of the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek, any head of a Choctaw household could register with the Indian Agent to be granted dual Choctaw and United States citizenship and to obtain legal title to land in Mississippi proportional to the size of his household.

Following the Treaty, large numbers of Choctaw people came to the Indian agent, William Ward in order to register and claim their Treaty right to stay on their own lands. Ward refused to register nearly all of the hundreds of Choctaw people who came to him, sometimes going into hiding (DeRosier 1970:135) and even threatening applicants with physical violence (Debo 1961:69). As a result, Article 14 of the Dancing Rabbit Creek Treaty was simply not honored. In the meantime, swarms of land-hungry AngloAmericans and their slaves rushed into Choctaw country and numerically overwhelmed the Choctaw people still there. Lands improved by Choctaw people for centuries were sold to the newcomers by the federal government, oftentimes literally right from under the feet of Choctaw families.

In 1842, Congressional investigations began into the conduct of William Ward and rampant land fraud. These investigations were not fully concluded for more than 60 years. In 1845, as a partial result of investigation, Congress granted some of the Choctaws who remained in Mississippi script for the amount of land they were entitled to under the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek However, the full amount of script was redeemable only in Indian Territory (Oklahoma). Some Anglo-Americans quickly found ways of defrauding Choctaw people out of this script. Businesses were even set up for that sole purpose (Reeves 1985:225).

Some Anglo-Americans used increasingly brutal tactics. Choctaws who remained in Mississippi had their houses burned down, fences destroyed, and cattle sent in to graze down their growing gardens. They were physically abused, chained, and even beaten to death (Tolbert 1958:66-67).

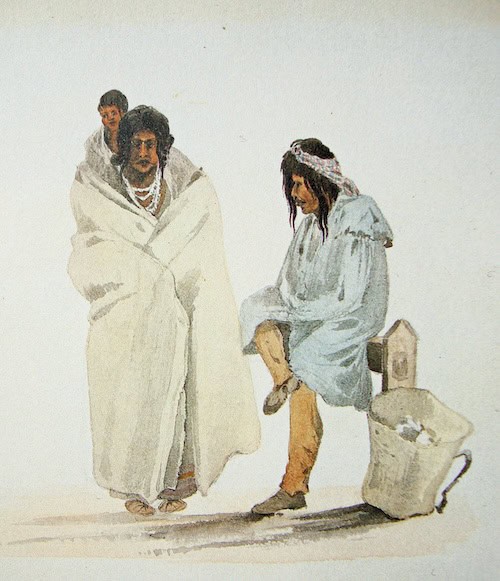

Under such treatment, perhaps 4,000 Choctaws removed from Mississippi to Indian Territory during the government-sponsored Removals of the 1840s. Still 2,000 Choctaw people simply refused to remove from their homeland. The price that these people paid to resist Removal was astronomical. They were forced into the most marginal land, and made their living as tenant farmers, or workers on Anglo-American plantations in racially segregated Southern society. Facing discrimination and abuse, they drew into their own communities and maintained traditional Choctaw life as best they could.

The final part of the Choctaw Trail of Tears occurred in 1902 to 1903 when 1,426 Choctaws were moved to Oklahoma. These individuals as well as those who had traveled west before became the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma. Choctaws who still remained in Mississippi and Louisiana would eventually become the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians and the Jena Band of Choctaw Indians.