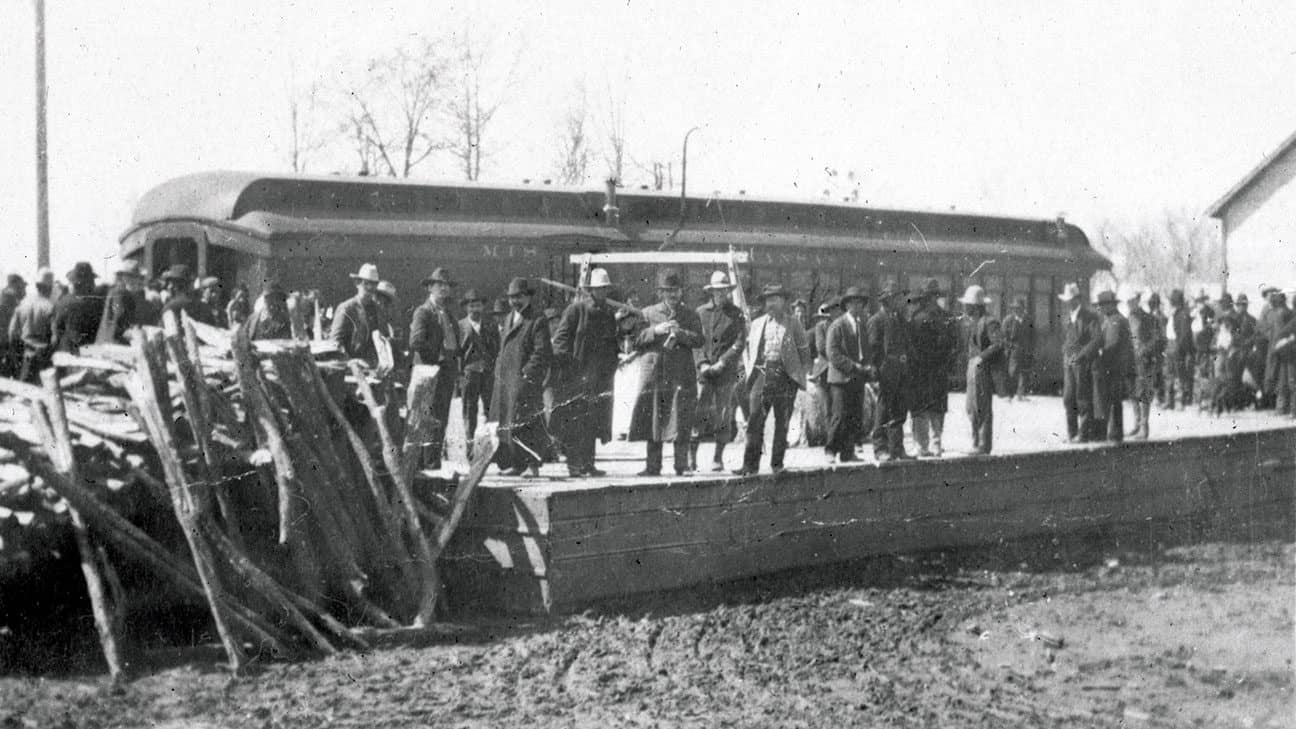

Crowds waiting to register for their allotments outside the railcar set up for the Dawes Commission.

A New Chahta Homeland: A History by the Decade, 1900-1910 (Part II)

Iti FabvssaPublished December 1, 2021Iti Fabvssa is currently running a series that covers the span of Oklahoma Choctaw history. By examining each decade since the Choctaw government arrived in our new homelands using Choctaw-created documents, we gain a better understanding of Choctaw ancestors’ experiences and how they made decisions that have led us into the present. This month, we will be covering Part II of the 1905-1910 period, when Choctaws were preoccupied with the creation of citizen rolls, allotment, and Oklahoma statehood.

In 1889, the “Unassigned Lands” (present-day western Oklahoma) opened to white settlement in an event now known as the Oklahoma Land Run. Authorized by the 1862 Homestead Act, settlers were allowed to claim 160 acres of public land and receive title to it after five years of working and living on that parcel of land. Originally, these lands were reserved for the possible relocation of Plains nations, but with increasing demands for land by Americans, Congress redesignated this land for settlers. After the infamous April 22 land run, Congress passed the Organic Act of 1890, which organized those lands into “Oklahoma Territory.” Before any place could be made into a state and brought into the United States, it first had to meet the requirements to be a U.S. territory. After fulfilling another set of requirements, a territory could become a U.S. state and join the United States of America. The territorialization of Oklahoma Territory, a major step toward statehood, only increased the pressure on the Five Tribes to allot their lands in neighboring Indian Territory (present-day eastern Oklahoma), especially with the increasing influx of white intruders entering their lands. The move towards combining Oklahoma and Indian Territories into a single state seemed inevitable after the proposed State of Sequoyah failed to pass Congress in 1905, which was reviewed in last month’s Part I of the 1900-1910 period of this series.

In 1906, Congress passed the Five Tribes Act as part of an effort to further assimilate their citizens into U.S. society by changing how tribal governments operated. It did this by moving control over numerous offices from tribal governments to the U.S. government. For instance, the U.S. became responsible for land offices and the entire school systems that the Five Tribes had built since their arrival in their new homelands. Although the Five Tribes Act tried to end the governments of the Five Tribes, that section was repealed with later legislation. Another important change came from Section 6 of the Five Tribes Act, which stated that if any of the Five Tribes chiefs refused or neglected to do his duty, he may be removed, and the U.S. President would fill the vacancy. This legally allowed the President to begin appointing every chief not long after the act’s passage. Although we do not review all the parts of this act here, it is still an important piece of legislation that affects Choctaws today.

The Five Tribes Act also set March 4, 1907 as the closing date for the Dawes rolls. After that date, no additional citizens could be added to the rolls. As mentioned in Part I, the Dawes Commission was responsible for developing Choctaw rolls to give allotments to every citizen. Not all the lands owned by Choctaw Nation were allotted. Townsites, timberlands, coal and mineral lands were all exempted from allotment. These lands that were not included in the allotment process were to be sold by the U.S. government. The proceeds from their sale would later be distributed to Choctaw and Chickasaw citizens in the form of per capita payments. Because of massive pushes by U.S. citizens and members of Congress to complete the allotment process in Indian Territory, the Dawes Commission had not even completed the final rolls for the Five Tribes before they had to start issuing allotment parcels to individual citizens. This only increased the chaos and disorganization of the process. The next major task was dividing the lands into allotments and assigning them to people.

When Choctaws received their allotments, some of the allotted lands were good for farming and some were not. Because of this, allotment sizes were determined by the quality and value of the land. Since Choctaw and Chickasaws were united by treaty their lands were evaluated together. All Choctaw-Chickasaw allotment parcels had an average value of 320 acres, meaning that after getting the value of all the Choctaw-Chickasaw lands and dividing it by the number of citizens, this was the equal value of the land. In practice, this meant that sometimes an individual would get 500 acres of rocky and unfarmable land while another person might get 80 acres of very good farmland. Sometimes people received parcels of land that were in completely different places than where they lived at the time of allotment. Choctaw-Chickasaw allotments were also divided into two categories: homestead and surplus. The logic behind this organizational method was that Choctaws would have land to live on land (homestead) and land on which they could improve upon for financial gains (surplus).

Another important fact about Five Tribes’ allotments was that they were held in a special legal status, “restricted.” The restricted status prevented Choctaw individuals from being able to sell, lease, or effectively manage their allotted land without the approval of the Bureau of Indian Affairs. The logic behind making allotted lands “restricted” was that the federal government believed Native people were not smart enough to understand how to manage their lands properly. Therefore, they needed government supervision for how they managed their lands. Many educated members of Choctaw society who ran their own businesses often vehemently opposed these restrictions because they undermined their ability to manage their own affairs. These restrictions would become a major point of contention and would be continually renegotiated and renewed for certain groups of Choctaws decades after the original 1898 Curtis Act, which outlined the original terms for restrictions.

There were also different groups of people who received allotments with different sets of conditions. For instance, orphaned children and individuals with disabilities often needed guardians for their allotments. This proved to be an area in which white men took advantage of Five Tribes citizens to gain more lands and make money for themselves. There are accounts of numerous white men who became professional guardians that would manage the lands and money of numerous Choctaws with restrictions for a profit. In 1908, Congress passed legislation that changed the jurisdiction of Indian minors’ estates from federal courts to Oklahoma probate courts. Those familiar with Oklahoma probate courts opposed this shift, arguing that these children’s cases would be plundered. These protests went unheeded, and the prediction came to pass. These issues would continue through the 21st century to the detriment of many of their descendants today.

Despite generations of Choctaws that fought against their incorporation into the United States, Indian Territory was combined with Oklahoma Territory, and on November 16, 1907, Oklahoma became a state and joined the United States. With Choctaws’ lands allotted despite great opposition, Choctaw society in the new homeland fundamentally changed. One of the intents behind allotment was to separate and weaken the Choctaw community. But despite all these major events, Choctaws worked to prevent that. Next month, we will look at the various ways that Choctaws continued to meet and organize to demand that the U.S. government fulfill its treaty and other legal obligations even though many of the powers of their government had been stripped away.