Remembering the Choctaw cultural revitalization movement

Published May 1, 2023By Shelia Kirven

A cultural revitalization movement led by Choctaw tribal members is responsible for bringing lost Choctaw traditions back to Oklahoma.

It began in the 1970s with Presbyterian youth and their families visiting Mississippi to study Chahta dance, stickball, beading and other traditions. The group returned to their roots to explore the deep culture of the past, bringing back traditions practiced generations ago by their ancestors.

Reverend Gene Wilson

Presbyterian minister Rev. Gene Wilson retired in 2005 but has wonderful memories of taking Choctaw youth and their families on yearly trips to the Mississippi Choctaw Fair, a week-long celebration of Choctaw culture.

He obtained a Presbyterian Faith and Identity grant and administered a needs assessment to determine the congregations’ needs. The overwhelming response was to learn more about Choctaw culture.

Wilson traveled to Mississippi on the first trip with two other staff members, John Bohanon and Levi Samuel, to organize trips for the youth.

According to Wilson, when they opened the trips up to others, they had tremendous responses from the young people and their families. Wilson remembers talking to a lady about early Choctaws and their rituals.

According to Wilson, the woman said, “We don’t talk about that; we don’t talk about that at all.”

Wilson said the traditions were kept by older people but weren’t shared with younger generations.

“The church did caution about dancing, and that carried even to the point of Choctaw dances,” said Wilson.

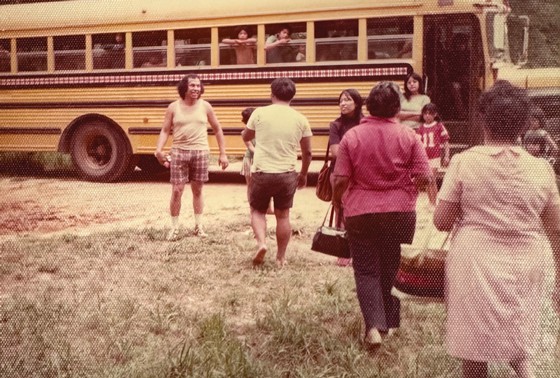

By the second and third years, the group took a van and a school bus to fit everyone who wanted to go.

The Presbyterian grant partially funded the excursions, but the local churches raised money for the trips. According to Wilson, the Mississippi Choctaws always helped with arrangements.

“They were open and enabled us to participate,” said Wilson.

Upon returning from the trips, they intended to do activities among themselves. However, they began getting invitations from within the communities to share their knowledge.

“The Choctaws themselves, I think, were renewed and began to form a new source of identity of who they always had been, and I think that’s how the older people and the church people received the young people who did the dances, to begin to receive them as an expression of visual, but also internalized identity of who we are as a people,” Wilson said.

One thing that was brought back from the trips was making traditional clothing.

Wilson remembers Helen Walton of Walmart coming to Idabel and enabling the Idabel Walmart to stock the clothing, needles, threads, ribbons and even hats they needed to make traditional clothing.

The group used the clothing for presentations, but some even wore it outside the functions. Eventually, tribal leadership started wearing shirts that reflected the culture.

The group also began participating in stickball events and taking week-long trips to Dwight Mission in Sequoyah County, Oklahoma, to play against Cherokee Nation players. They were even invited to Canada to sleep in a teepee and participate in tribal dancing.

Other groups formed as the youth grew up, and they carried out the traditions they had learned years before. Some participated in dance groups and became powwow dancers, traditional clothing makers and artists.

For Wilson, the most important thing resulting from the trips was internalizing their own identity.

“It’s not an individual identity. It’s the group Choctaw identity,” said Wilson.

It makes him proud to have been part of the revival of bringing Choctaw culture back, but he gives credit to the youth.

“The little ones should deserve all the credit,” Wilson said.

The Billy Family

Teri Billy and Charles Battiest were college students who became interns under the leadership of Gene Wilson, their minister with Choctaw Presbyterian Larger Parish.

With a focus on youth ministry and activities for the youth, they began going on the Mississippi trips in the second year.

“The L.A. riots had just occurred a few years before, and the stand-off at Wounded Knee created a heightened awareness of cultural identity and cultural awareness,” said Teri. “Relearning our culture was in the midst of the social and cultural change that was occurring.”

Teri’s husband, Curtis Billy, often reflects on his and Teri’s youth.

“Presbyterians were more into the social and educational aspect of ministry as well. So, we benefited from just growing up in that system,” said Curtis.

At the time, many churches in the area wanted to focus on just the gospel and not social activities.

“The Presbyterians were different and more liberal in that sense. So that’s the kind we grew up in,” Curtis said. “We knew we were Choctaws; we have a language, we did church activities, but they realized when they got around others like Plains Indians, we didn’t have any dances or those types of things that are part of us, that we haven’t revitalized in a while since statehood.”

During that time, civil rights movements were happening, as well as the occupation of the American Indian Movement. College campuses were demanding more accountability and non-traditional education.

“That was kind of the mood, and it just spilled over into our Native world,” said Curtis. “The benefits that came out of that, there were several grants available by corporations and companies, and educational colleges started providing scholarships beyond what the BIA (Bureau of Indian Affairs) was providing for Indian Ed.”

According to Teri, when Native high school students graduated, they were told they were not college material and were encouraged to go to trade schools. The BIA started giving large grants to Native American students under pressure and protest, which is how many in that age group had the opportunity to go to college.

At the time of the cultural revival, Curtis was a senior in college and knew about data analysis and needs assessments when the trips to Mississippi were being planned.

“That prompted the needs assessment, and the kids wanted to gain more of their Choctaw identity, including culture, heritage dance, stickball, these things that we didn’t do anymore,” Curtis said.

According to Curtis, in Mississippi, they were beginning their revitalization with the Choctaw Fair. The Choctaws there still had remnants of those who did the cultural activities, but they were scattered.

“So that’s where Gene and his staff concentrated on planning with that tribe to explain what we were about and trying to revitalize our program and relearn things that had been lost,” said Curtis.

The Mississippi Choctaws scheduled dignitaries to meet with them and had top dance people teach them.

“We spoke the same language,” Curtis said. “They told us our dance instructions in Choctaw because they didn’t know how to explain it in English.”

Teri took notes, listened and interpreted, as she had been taught to read and write in Choctaw as a young child.

Curtis took photographs and made recordings of oral histories for the youth to study.

“We learned the dances, at least 10 or 12, but we weren’t good at any of them. It takes practice to become proficient at it, but we at least knew dance steps and what the meaning on the surface was,” said Curtis.

“To me, I was looking at the cultural implications within the dance process, so I captured all that.”

The Billy family went on the Mississippi trips for about ten years, taking their children as they came along.

According to Teri, Rev. Wilson started an organized dance group of adults and children. The group would perform at places like the Owa Chito Festival in McCurtain County.

Eventually, Curtis took a position in Miami, Oklahoma, with the Indian Arts and Crafts Program.

He was then hired at Broken Bow Schools in 1974-75 as a community liaison counselor/education counselor. Curtis formed the American Indian Youth Council at Broken Bow School.

Teri believes the school had the first, and possibly only, existing Arts and Crafts class one could receive credit for, which Curtis began (pottery, basketry, jewelry making, etc.)

Curtis worked for Broken Bow schools for 30 years, using much of what he learned in Mississippi to guide his career.

Curtis said, “We are still in the stage after 50 years of this, still teaching people and learning. Not everybody has gotten it yet. It’s optional, we’re not making anybody, but we want to make it available.”

For Curtis, the new Choctaw Cultural Center is an excellent vehicle for maintaining knowledge and displaying the culture.

“It doesn’t mean it’s where our culture is, it’s where you can see highlights of it, and it’s permanent,” said Curtis.

According to Curtis, it makes him feel good when he sees the celebration of our culture all over our reservation now. Curtis also credits Chief David Gardner (1975-1978) for wanting the groups to teach others what they had learned.

During his term in office, Gardner encouraged the cultural revival and wanted staff to wear Native dress and visit the homeland.

The McKinney Family

Julia McKinney and her family went on some Mississippi trips, and her children were involved with the dance group Curtis Billy formed at Broken Bow High School.

“The story that I had read was that when they left Mississippi on the Trail of Tears, that they left Choctaw dancing and a lot of the culture,” Julia said. “If it weren’t for Gene doing that [the trips], the dances would have never come alive again.”

Julia remembers the groups invited to dance at various schools and the Owa Chito Festival of McCurtain County in 1975.

She also remembers going on trips where they stayed at a church, slept on the floor and took their own food.

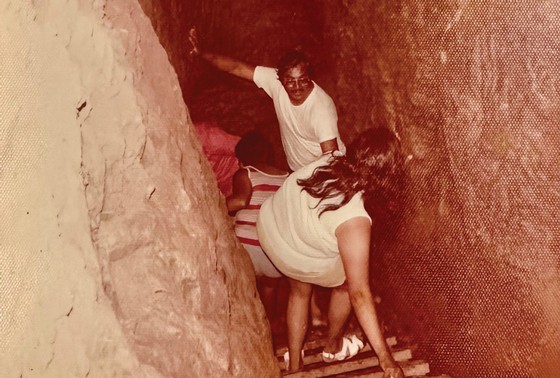

She recalls learning to cut dresses and shirts and watching stickball games and princess pageants. They all went to the Mother Mound. There was a cave no one else was entering, but Gene took the young people in it.

“They had a language department, and they were making films, but everything was in Choctaw, and I really enjoyed that too.”

Julia is a fluent speaker of the Choctaw language.

According to Julia, after they returned from Mississippi, the group wrote a grant through the church to Helen Walton, owner of Walmart stores. She came to Oklahoma and watched the cutting out of the dresses.

A few years ago, Julia was honored by an artist who proudly credited Julia for teaching her how to cut out dresses.

Family members still participate in the dance troupe, and many have been honored in various ways for their teaching and participation.

“Every year, our kids have been part of it, and our grandkids are still dancing,” Julia said.

Her children learned chanting from Jerry and Shirley Lowman, who learned it themselves in Mississippi throughout their years.

The McKinney family traveled with the dance group, and Julia made dresses and shirts for others, even for pageants.

Julia believes the original traditions were halted after the Trail of Tears. She said she asked her mother-in-law if she ever did the Choctaw dances. Her mother-in-law responded that her mother had spoken of dancing, but she wouldn’t show her how.

Julia, an Oka Achkma Presbyterian Church member, has written out some of the histories she has researched and shared them with church members.

“We have been involved in church all of our lives,” she said.

Julia’s son, Karl, fondly remembers going on the Mississippi trips and learning how to play stickball.

“It was not a matter of getting hurt, but it was a matter of how bad you got hurt.” Karl said, “The game has progressed to be less violent for the safety of the players.”

Present Day

Today, Choctaws honor their ancestors’ memories by remembering them through their customs and traditions.

Rev. Gene Wilson and his staff and family, the Billy family, the McKinney family, and all those who traveled to Mississippi, the Presbyterian Church, and Chief David Gardner are among the many who helped to bring Choctaw culture back to Oklahoma.

“Again, it’s all about identity and that time to be identified as who you are and be proud of who you are, and for the students it increased their self-awareness and self-concept,” said Curtis Billy. “In other words, it made us complete.”

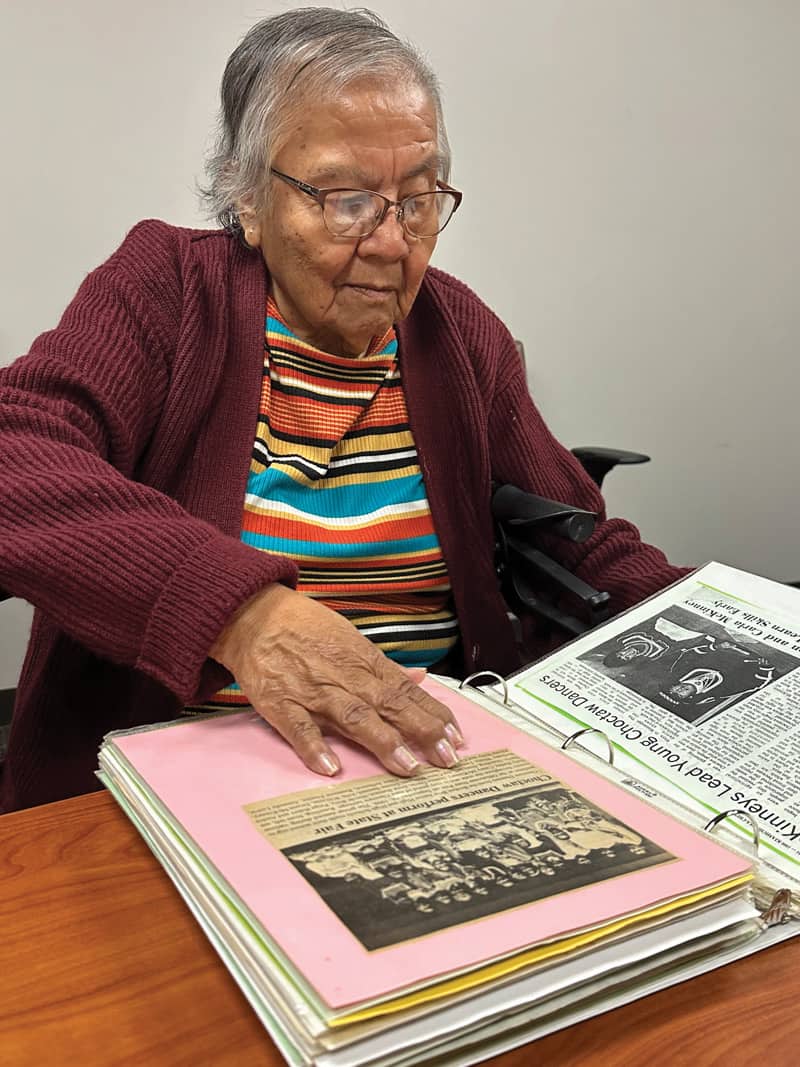

Julia McKinney looks through a scrapbook of memories from the days of the cultural revitalization movement and trips to Mississippi.