Provided by www.historyschoop.com

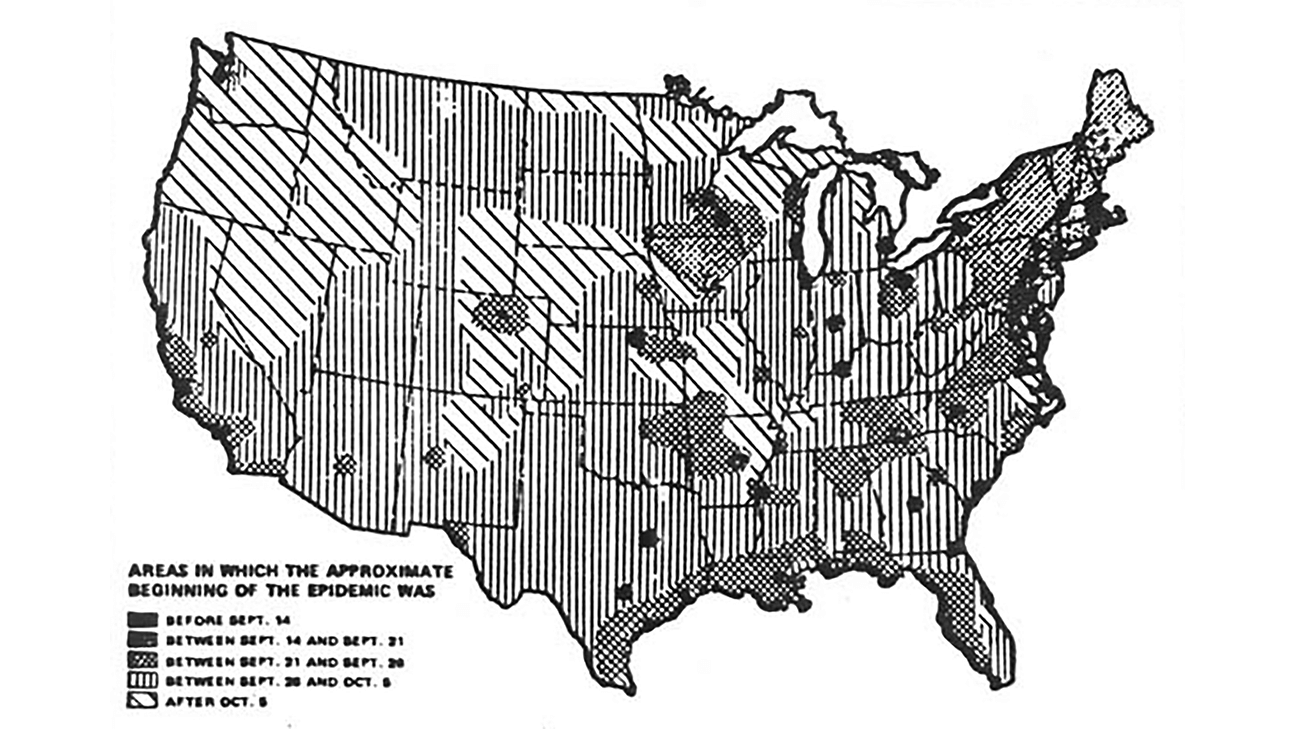

Provided by www.historyschoop.comThe map illustrates when different areas of the United States felt the beginning of the 1918 Flu Epidemic. The misnamed "Spanish" Flu struck quickly. A sawmill owner, Peter Conser, converted his sawmill to be able to produce coffins for tribal members, but could not keep up with demand. In some cases people in Choctaw communities were buried in sheets in mass graves. Choctaws used strategies developed by their ancestors to help survive the epidemic sweeping through the nation.

1918 Spanish Flu Hits Choctaw Nation

Iti Fabvssa

April 1, 2018

Exactly 100 years ago, April 1918, a deadly and unseen enemy entered the Choctaw Nation. We have all had the unpleasant experience of struggling through the flu, but the, erroneously named, Spanish flu strain that hit in 1918 was particularly cruel.

Accounts from the Choctaw Nation talk about so many people passing away so quickly from this strain of flu that there were not enough coffins for burial.

This disease would go down as the worst natural disaster in human history, yet it wasn’t the first time that the Choctaw people had faced something like this.

Overcoming past epidemics had taught the Choctaw people ways to be resilient. This month’s Iti Fabvssa will explore the history of the Spanish flu pandemic, how Choctaw people fared during the three waves of this illness and demonstrate how the Choctaw community had learned to battle disease in the years before Tamiflu.

When the Spanish first entered what is now the Southeastern United States, they brought diseases that had never been seen in the region before.

Ranging from smallpox to the flu, the effects on Native American communities who had never built up resistance to them were devastating.

From the 1500s through the 1700s it’s estimated that 90 percent of the Native population in North America died from European disease. Choctaw people were not able to avoid this.

Many tribes in the southeast were lost; however, Choctaw ancestors developed strategies that helped them to survive the onslaught of disease.

Family and community members would care for the sick and ensure they were provided for with proper food, water and other comfort, which gave them better odds of survival.

Choctaw communities soon recognized that the rivers, which brought people to and from their villages, were corridors for the spread of European diseases.

In response, many of them relocated from areas like Mobile Bay and the Alabama River to the core of the old Choctaw homeland, around Nvnih Waiya, a region that is not easily accessible by boat.

Finally, Choctaw communities often adopted and integrated other tribal people that came from other devastated communities.

This practice helped Choctaw people recover population loss during the waves of illness and also helped disease-weakened communities to protect themselves from having their fields burned by enemies, which would have made recovery from disease even more difficult.

All of these strategies, isolation, adoption and particularly directly caring for the sick, helped Choctaw people face the Spanish flu when it hit in 1918.

The “Spanish” flu was not Spanish, nor did it originate in Spain. During World War I, the government censored all media coverage from the United States, including the seriousness of the impending flu pandemic to avoid affecting morale within the troops stationed abroad.

Since Spain was neutral during the war, Spanish media covered the spread of the flu, its aggressive nature and the rising death toll in full detail.

The entire world assumed it was the country of origin, but it actually may have started not too far from our Oklahoma border.

The first reported case in the United States came in April 1918, in Haskell County, Kansas (Gunderman 2017).

Service men from Haskell County reported to Fort Riley and the disease quickly spread through the entire camp.

The first wave waned with the deaths of several dozen soldiers in Kansas. It was the second wave, during the fall of 1918, which proved to be the deadliest.

Crowded military bases, encampments and hospitals during World War I provided the ideal location for the development of the aggressive flu strain.

Once soldiers began to return to the United States they quickly spread the deadly strain virus to their friends and family.

The first of these cases was reported near the Boston harbor in the summer of 1918. The flu virus was so rampant that at one point over 1,500 soldiers were diagnosed within a single day.

This would become the norm for the next two months across the nation. The difference between the first and second waves was the acceleration of symptoms with many individuals experiencing symptoms in the morning, only to pass away that evening.

The disease was particularly lethal to young, healthy people.

Entire cities shut down. “The most basic public services were crippled or even closed,” including emergency rooms, hospitals, pharmacies, grocery stores, police stations, waste management, transportation and government offices of any kind (Smith-Morris 2018).

Historical reports have helped to piece together the spread of the second wave across the nation (see illustrated map above).

From this, we know the flu arrived in Oklahoma in September of 1918 with a vengeance, roughly between Sept. 21 and Sept. 26.

After first contact in the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma the virus spread to adjacent counties and cities, including Tulsa and Clinton (Keeping 2015). By Oct. 4, 1918, over 1,249 cases of influenza were reported in 24 counties in the State of Oklahoma.

By this date, there were at least 291 deaths reported in Pittsburg County, 100 in Pushmataha County and 250 in Antlers. The final death toll was calculated at nearly 7,500 people across the state by the spring of 1919 (Keeping 2015).

In an effort to contain the flu, on Oct. 10, 1918, Dr. J. D. Duke, the State Health Commissioner, issued an order to close all schools, theaters, church services and other public gatherings across the entire state to avoid further spread. This struck fear across Oklahoma.

Despite fear of catching the flu Choctaw communities attempted to offer the most basic of needs and comforts to their families and friends in the form of warm blankets, adequate nutrition and home remedies. Often times, this meant Choctaw families remained isolated for weeks at a time.

As the death toll climbed in the state, communities in the Choctaw Nation felt the loss. Peter Conser converted his sawmill into producing coffins for tribal members, but even he could not keep up with the demand.

At the peak of the pandemic, Choctaw communities made the hard choice to bury their friends and family in sheets in unmarked mass graves.

The Spanish flu also struck Choctaw communities living in other areas. When it hit Mississippi it quickly killed 25 percent of the Mississippi Choctaw community (Carleton 2002:2).

Today, two large cedar trees serve as markers for the nearly 1,000 Mississippi Choctaw buried in the center section of the Holy Rosary Mission cemetery (Neshoba Democrat 2014).

After the news of the initial impact to the Mississippi Choctaw community reached Washington D.C., the federal government stepped in to offer aid and support to prevent the complete loss of the entire community (Carleton 2002:2).

The Spanish flu also hit Choctaw communities in Louisiana.

Survivors talked about entire households passing away from the disease.

For Choctaw people, the loss was not only in human terms, but also in terms of knowledge.

In a culture that had already been marginalized through colonization, the loss of a few key people could destroy important pieces of traditional knowledge and skill.

For example, some traditional Choctaw basketry techniques seem to have died out when highly skilled basket-makers succumbed to the Spanish flu.

The Spanish flu hit as a third wave in 1919, then subsided almost as quickly as it had come. Government research across the country sought to identify what medicines or treatments were most successful against the Spanish flu.

What they found was that it was not any particular medicine that gave people the best chance of survival, but rather it was simply having someone there to care for them, making sure they had access to water, providing a blanket to them, giving them lemon juice, etc.

Most of the Choctaw family stories that have come down to us about the flu of 1918 talk about Choctaw people doing just that, carefully tending the sick, then cooperatively working to help their communities rebuild.

To them such behavior, learned through past experience with disease, was an important part of our Choctaw faith, family and culture. It continues to be today.

About Iti Fabvssa

Iti Fabvssa seeks to increase knowledge about the past, strengthen the Choctaw people and develop a more informed and culturally grounded understanding of where the Choctaw people are headed in the future.

Additional reading resources are available on the Choctaw Nation Cultural Service website. Follow along with this Iti Fabvssa series in print and online.

Inquiries

If you have questions or would like more information on the sources, please contact Ryan Spring at [email protected].