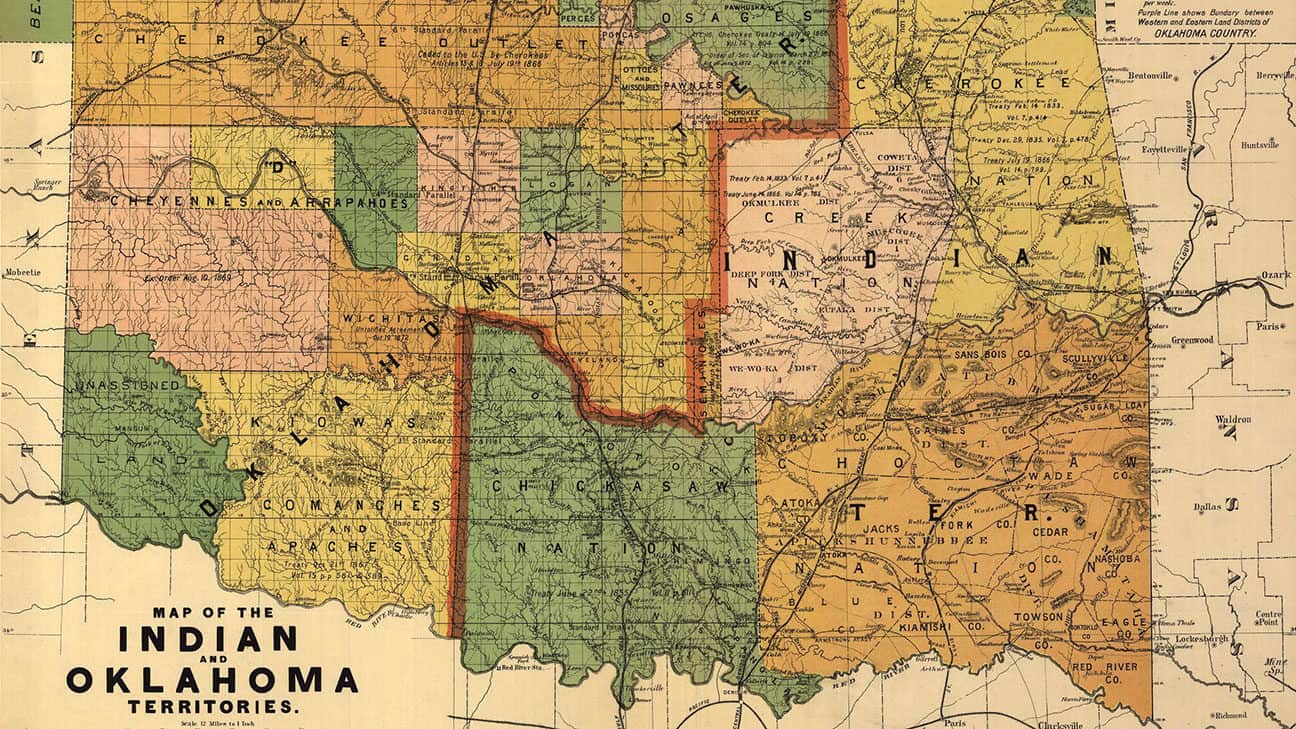

The Indian Territory (now eastern Oklahoma) and the Oklahoma Territory (now western Oklahoma) were combined to form the State of Oklahoma on Nov. 16, 1907.

Oklahoma History Supplemental

Published October 3, 2020

Overview

In July 2020, the U.S. Supreme Court issued a ruling in a case called McGirt v. Oklahoma, that reaffirmed the treaty rights of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation. Someday we may look back on it as being one of the most important turning points in the history of Oklahoma, and of its tribes.

This “Oklahoma History Supplement” to your textbooks tells the story from the vantage point of the Choctaw Nation.

The Five Civilized Tribes

The Choctaw, Chickasaw, Cherokee, Muscogee (Creek), and Seminole Nations are all large Native American tribes whose original homelands were located in the southeastern United States. After European-Americans arrived in what is now the United States, they sometimes referred to these tribes as the “Five Civilized Tribes” because their economies were based on agriculture.

In the 1830s, each of the Five Civilized Tribes signed treaties with the United States that removed them from their homelands and brought them to Indian Territory—in what is now Oklahoma.These treaties stated that the Five Tribes would never become part of the United States or any of the states within it. Instead, each tribal government would continue to have sovereignty over its own lands, peoples, and borders. Such tribal lands are legally considered a reservation.

The Choctaw Nation had been an ally of the United States since the American Revolution, and continued conducting business with Americans after Removal. If people who were not Choctaw tribal members respected Choctaw laws, they could visit the Choctaw Nation, work there, or even become Choctaw citizens. The Choctaw government did everything within its power to ensure that their way of life continued in their new lands. But things drastically changed with the U.S. Civil War.

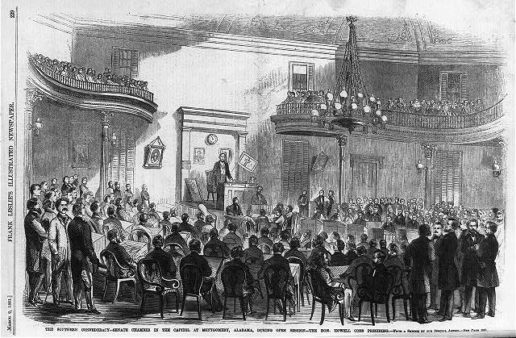

The Choctaw and Chickasaw nations sent a delegate to the Confederate Congress in Richmond, Virginia. They also organized battalions of warriors to help the Confederate Army keep peace and security in the Indian Territory. After the Civil War ended, the tribes signed a surrender treaty which imposed harsh conditions.

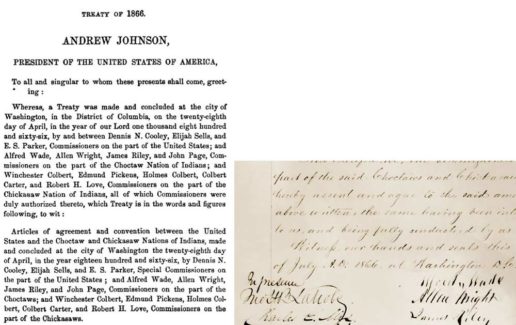

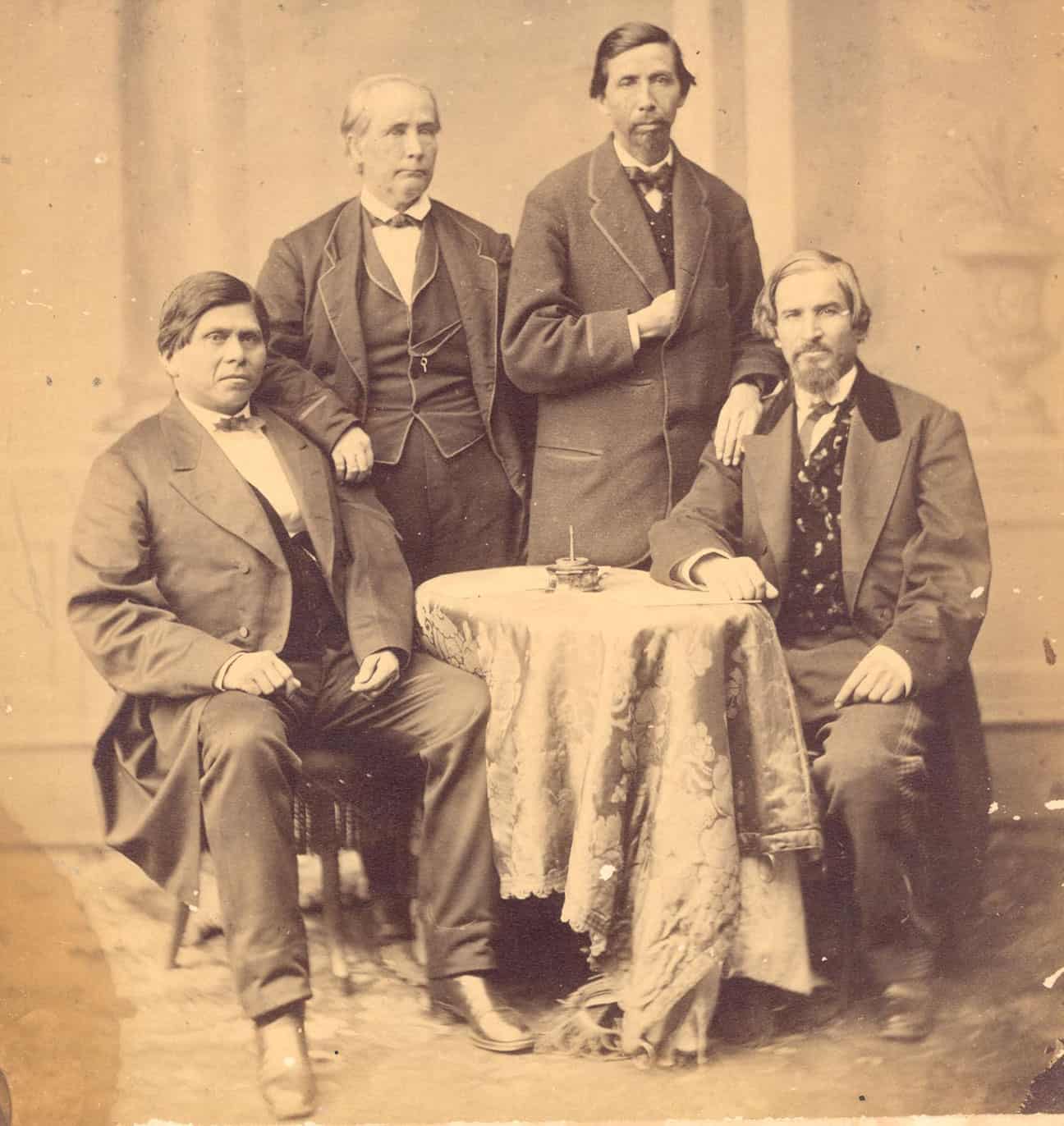

Principal Chief Allen Wright, shown at left, with the Choctaw negotiating team in Washington, D.C. The surrender treaty they negotiated with the United States included provisions weakening tribal sovereignty which they were unable to remove.

The War between the States

As war broke out between the Union and the Confederacy, Union troops and federal agents retreated from the forts built to protect Indian Territory. The Choctaw and Chickasaw Nations had little choice but to side with the Confederate States of America in the conflict. Their safety and security were at stake.

After the U.S. defeated the Confederacy, the Five Tribes all signed new treaties with the United States in 1866. Because the Tribes had sided with the Confederacy, the U.S. forced them to accept concessions that included the loss of land and some of their control over their lands. The most significant requirement was the allowance of railroads to be built within and through Indian Territory.

The Railroads

The Missouri, Kansas, and Texas Railway, completed in 1872, was the first railroad to cross the Choctaw Nation. A rapid influx of American settlers accompanied the railroads into Indian Territory. This changed the population dynamics of Choctaw Nation since there were many non-Choctaw citizens now within its boundaries.

At the same time, American settlers were pushing to acquire lands set aside by the U.S. government for Tribes. By 1889, land runs were beginning to be held west of Indian Territory. Congress was also making its own plans for dividing up Indian lands to gain access to natural resources, profit from selling land, and assimilating Native American people.

Senator Henry L. Dawes of Massachusetts directed the Commission to the Five Civilized Tribes, also known as the Dawes Commission, which was charged, sometimes secretly, with taking whatever steps were necessary to eliminate the Five Civilized Tribes' governments, domains, and sovereignty.

Allotments and The Dawes Commission

In 1887, Congress passed the General Allotment Act, which divided tribal lands into individual parcels known as “allotments”. Most Tribal Nations owned their land in common, which meant no single individual had exclusive rights to land. This ensured that every community member had a place to live and grow food for themselves and their families. The United States wanted to issue allotments to make tribal people private landowners in order to assimilate them into American society. After the U.S. government passed the Curtis Act in 1898, Choctaws were forced to accept allotment and move towards ending their tribal governments.

The Dawes Commission was formed by Congress to create rolls of tribal citizens who would be provided allotments of land. Once all land was allocated to the Native Americans on these rolls, the United States would sell the remaining lands to American settlers who wanted land in Indian Territory.

Before the allotment process began, representatives from the Five Tribes met at Muscogee, Indian Territory and developed a constitution to create a U.S. state that they called the State of Sequoyah. They submitted their constitution to Congress, but President Roosevelt rejected it, preferring that Oklahoma Territory (to the west) and Indian Territory join as one state.

We now know, from historical documents on file in the National Archives, that the Federal Government did not always negotiate in good faith with Tribal Nations. The Dawes Commission was ordered to engage the tribal governments in discussions on their future. The commissioners were secretly authorized to take whatever steps necessary to eliminate those governments, so that allotment could proceed, resources could be acquired, and land could be sold.

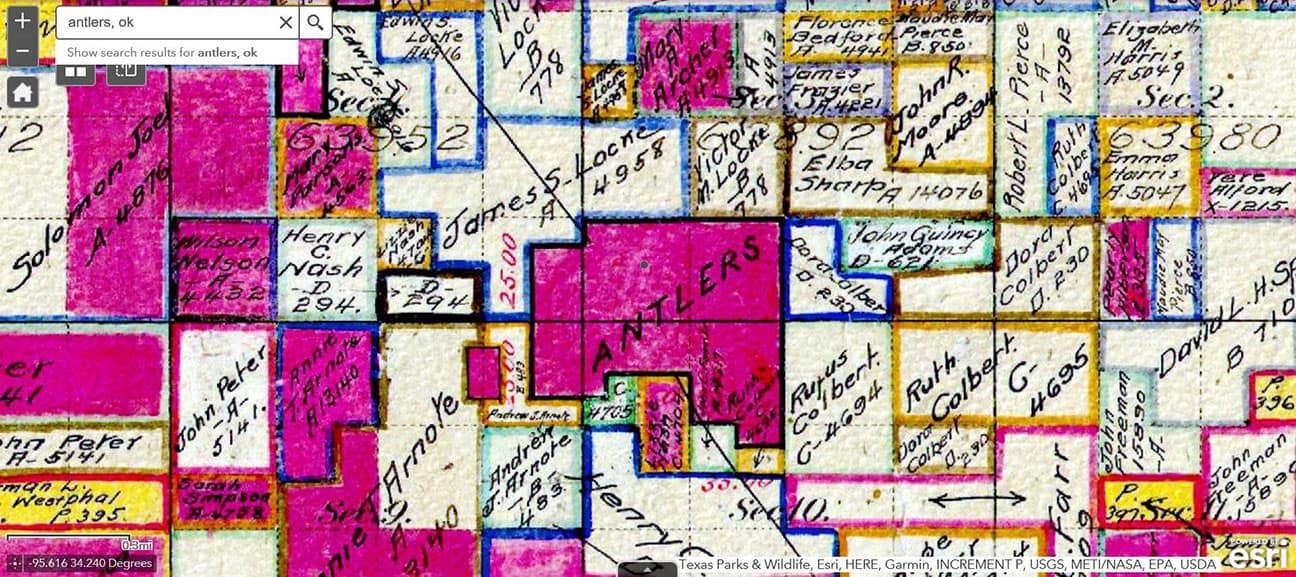

This map shows allotments to individual Choctaw tribal members in the area around what was then known as Antlers, Indian Territory.

The allotment of the lands of the Five Tribes took place in waves, beginning in 1893 and ending in 1907. It extended across four different Presidential administrations and six successive Congresses. What now may seem like an orderly process was filled with indecision and disorder. At one point the federal government, wanting faster action, ordered the Dawes Commission to begin allotting the land even before it had finished compiling the final tribal rolls.

During the process of allotting land, U.S. government investigators reported allegations—which they believed to be true—that federal officials in the Indian Territory were engaging in conflicts of interest by becoming involved with land development companies. These companies stood to earn a lot of money if allotment concluded. More than a century later, the Choctaw and Chickasaw Nations would receive One hundred eighty six million dollars ($186,000,000) in a settlement for this land fraud.

The Bureau of Indian Affairs, the U.S. government office that managed Choctaw allotments, often did not have sufficient staff, leaving Choctaw individuals vulnerable to oversight and unscrupulous individuals who swindled them out of their land allotments. Another problem was that some of the allotments were not livable. Some tracts had no water, and others were widely separated parcels. Also, Indians receiving allotments were given impossible requirements like having to have their home built on their new property within a week. This led many to sell their land for a fraction of its value.

With statehood looming, Congress planned to terminate the tribal governments in March 1906, a year and a half before statehood. It chose to leave small tribal administrations in place to help close out the tribes’ unfinished business. The idea was this would occur soon after statehood, and the tribal governments would then go out of existence.

The Five Tribes and their lands were never disestablished by Congress. Before any of the Five Tribes could be disestablished, their government affairs had to be settled. For example, the Choctaws and Chickasaws owned almost a half-million acres of immensely valuable coal, asphalt, and timber lands that had to be sold before they were officially disestablished. Questions regarding these lands and other financial interests proved tricky to settle, in part due to poor administration and recordkeeping by the federal government.

In 1906, elective government ended for the Choctaw. The office of Chief continued as a presidentially appointed position until 1970. In 1971, Choctaw voters elected their first Chief since statehood. In the 1980s a new constitution was drafted that placed legislative authority in the hands of the newly formed Tribal Council. Since then, the Choctaw Nation has gone through a renaissance.

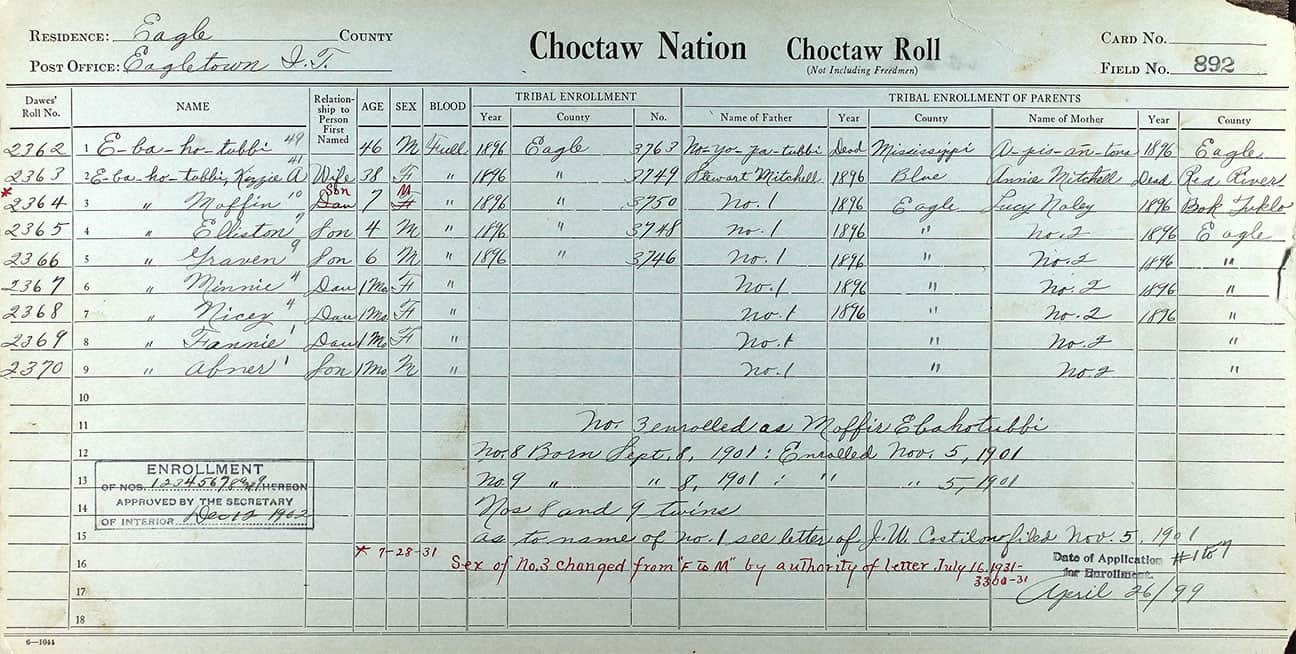

The federal government disregarded the tribes' own citizenship rolls and created its own, which it declared to be binding. Shown here is an enrollment card for a member of the Choctaw Nation.

Oklahoma became a state on Nov. 16, 1907.

Landmark Court Cases

In 2000, the State of Oklahoma convicted Patrick Murphy of murder and sentenced him to death. Murphy, a Muscogee (Creek) Nation tribal member, later challenged the state’s jurisdiction arguing the murder occurred within the Muscogee (Creek) Nation reservation, which he claimed still existed. The Major Crimes Act states that only the federal government has jurisdiction over crimes like murder, robbery, or burglary committed by Native Americans on Native American land, Murphy used this argument in an attempt to get his conviction thrown out. This case became known as Carpenter v. Murphy.

Murphy’s challenge rose to the U.S. Supreme Court in 2019, which heard the case but failed to come to a verdict. The court announced it would retry the case in 2020, but instead chose to set aside Carpenter v. Murphy in favor of a similar case, McGirt v. Oklahoma.

Jimcy McGirt, a member of the Seminole Nation, was tried and convicted by the Oklahoma state court for crimes committed in the Muscogee (Creek) Nation. Jimcy McGirt was sentenced to life in prison. McGirt appealed the state’s conviction and his case, known as McGirt v. Oklahoma, reached the U.S. Supreme Court. In a split decision, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in July 2020 that the Muscogee (Creek) Nation reservation was never withdrawn and still exists today The McGirt decision is one of the most important Indian law cases for Oklahoma tribes, especially the Five Tribes, in recent history.

According to the U.S. Supreme Court, the State of Oklahoma had no authority to try either man, since their alleged crimes took place in tribal territory and they are tribal citizens. In legal terms, the state does not have jurisdiction over criminal law on reservation land. The court’s ruling pertained specifically to the Muscogee (Creek) Nation and is limited to matters of criminal law. Nevertheless, it affirms that the Muscogee (Creek) Nation is still reservation land.

What's Next?

Indian law experts say the Supreme Court’s finding is rooted in the language and legal underpinnings of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation’s Treaty of 1866 with the federal government. That treaty is very similar to the treaties also signed in 1866 by the Choctaws, Cherokees, Chickasaws, and Seminoles. If that is indeed true, the experts say, it may be only a matter of time before the court’s ruling is applied across all Five Civilized Tribes.

Discussion Questions

- What is a reservation and why is it important to a tribe?

- What was a major concession of the Five Tribes in the Treaty of 1866 and what was its impact?

- What was allotment and why did the U.S. government undertake this process?

- How did the Five Tribes respond to possible U.S. statehood?

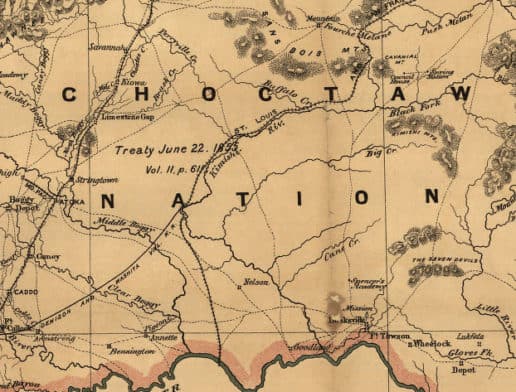

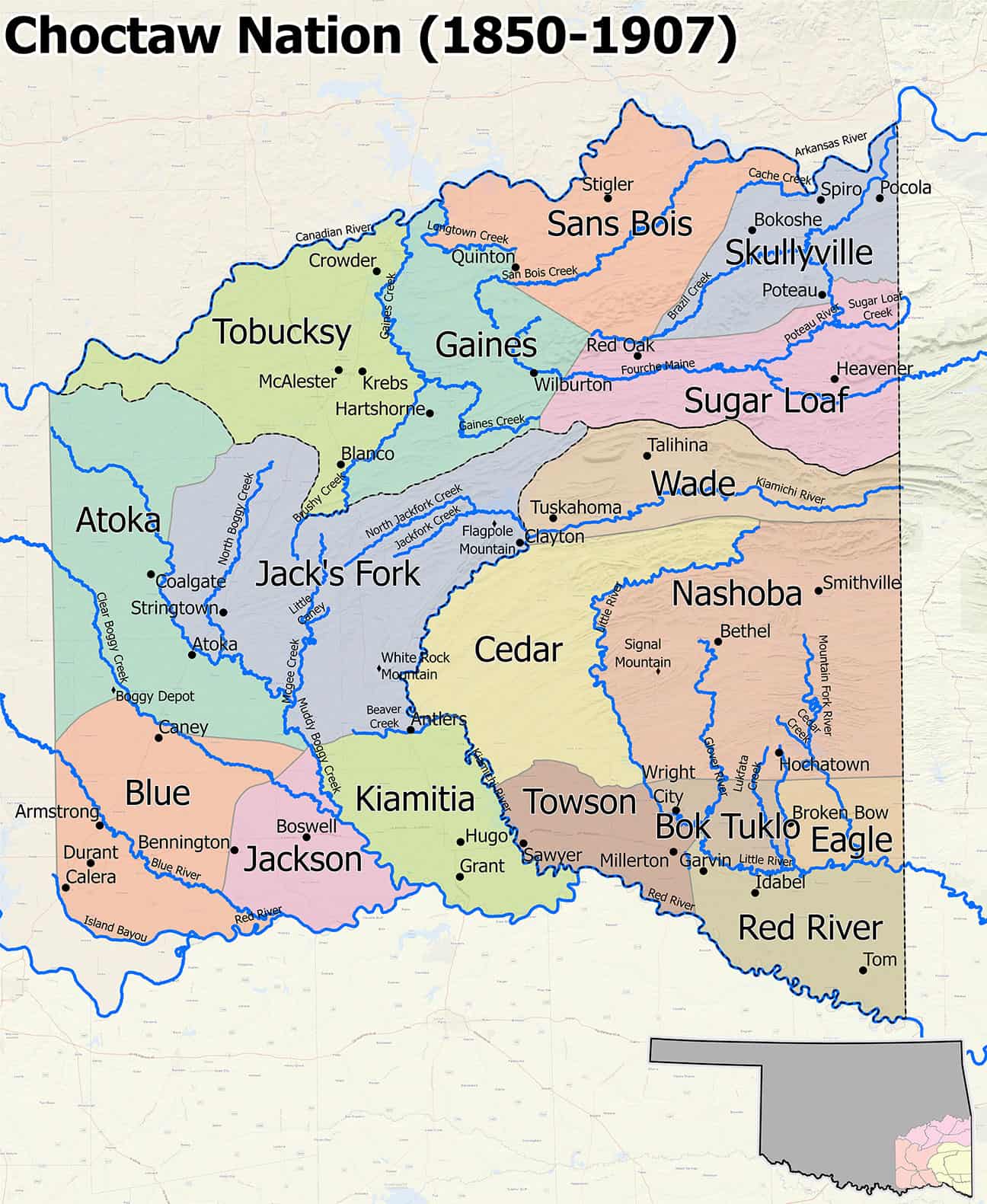

The Choctaw Nation, which had all the powers of a sovereign government before Oklahoma's statehood, divided itself into 19 counties. These are very different from the Oklahoma counties of today.

Additional Materials

Where was your town in the original Choctaw counties? Prior to Oklahoma’s statehood in 1907, the Choctaw Nation consisted of 19 counties. Unlike the counties of today, these were drawn using rivers and mountains as their borders. Oklahoma’s counties are very different. Locate your home!

The Choctaw Nation’s cartographers (mapmakers) have prepared beautiful maps of each of the 19 counties. Below are links to the maps, with the names of the present-day towns which would have fallen within the boundaries of each county.